TLS

TLS

Introducing TLS

It was originally designed for secure e-commerce. However, it is now used almost everywhere and it has become the de facto secure communications protocol of choice. Today, almost 100% of the Internet traffic is over HTTPS.

TLS is the IETF-standardised version of SSL.

In particular, TLS 1.0 in RFC 2246 (1999): translation of SSL 3.0. TLS 1.1 in RFC 4346 (2006): security tweaks. TLS 1.2 in RFC 5246 (2008): security tweaks, AEAD. TLS 1.3 in RFC 8446 (2018): major re-design.

High level goals

As per RFC 8446,

The primary goal of TLS is to provide a secure channel between two peer.

- Entity authentication:

- Server side of the channel is always authenticated.

- Client side is optionally authenticated.

- Using either asymmetric crypto (e.g.: signatures) or a symmetric pre-shared key.

- Confidentiality

- Data sent over the channel is only visible to the endpoints.

- TLS does not hide the length of the data it transmits, but allows padding.

- Integrity

- Data sent over the channel cannot be modified without detection.

- Integrity guarantees also cover reordering, insertion, deletion of data.

TLS aims to provide security even if the attacker happened to have complete control of the network.

Requirements

TLS only needs a reliable, in-order data stream.

Secondary goals

- Efficiency

- Attempt to minimise crypto overhead.

- Minimise use of public key techniques (as they’re less efficient) and maximise use of symmetric keys

- Minimise number of communication round trips before the secure channel can be used.

- Flexibility

- Protocol supports various algorithms and authentication methods.

- Self-negotiation

- The negotiation is done as part of the protocol itself.

- This is done through the version and cipher suite negotiation process:

- client offers, server selects.

- Protection of negotiation

- Aims to prevent MitM attackers from performing version and/or cipher suite downgrade attacks.

- So, the cryptography used in the protocol should also protect the choice of the cryptography made.

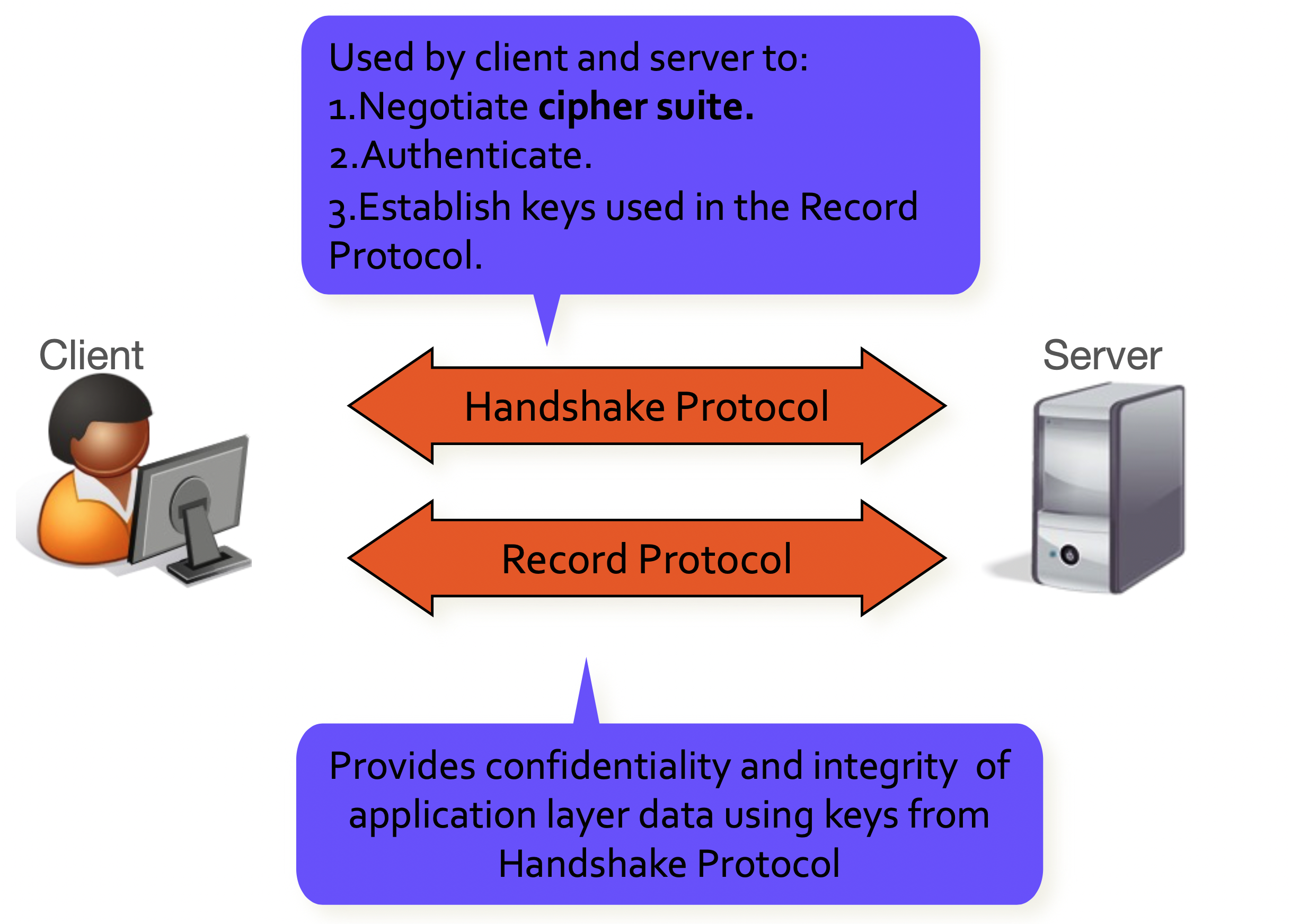

Simplified view of TLS

TLS 1.2

TLS 1.3

Motivation for TLS 1.3

TLS 1.2 was filled with vulnerabilities in every part of the protocol. The implementations were of poor quality. The attacks targeted protocol-level and implementation-specific vulnerabilities.

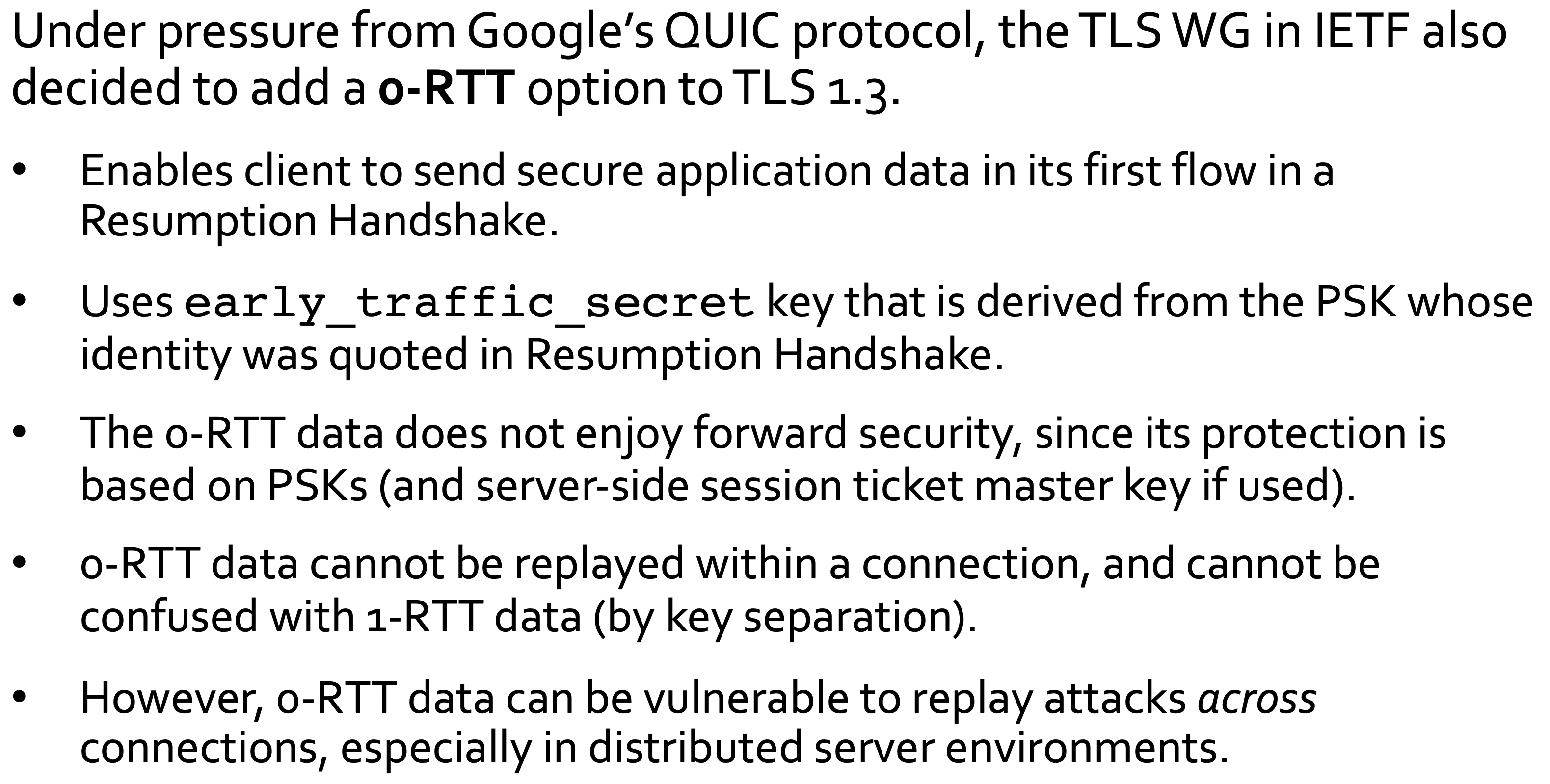

Google developed QUIC (which runs over UDP), which had several advantages over TLS 1.2, especially with respect to the number of RTT communications (50-200ms) before the establishment of the secure channel. TLS 1.2 was a 2-RTT protocol, and, if you add (the mandatory) TCP, you get a 3-RTT protocol.

TLS 1.3 mimics QUIC in achieving same RTT profile.

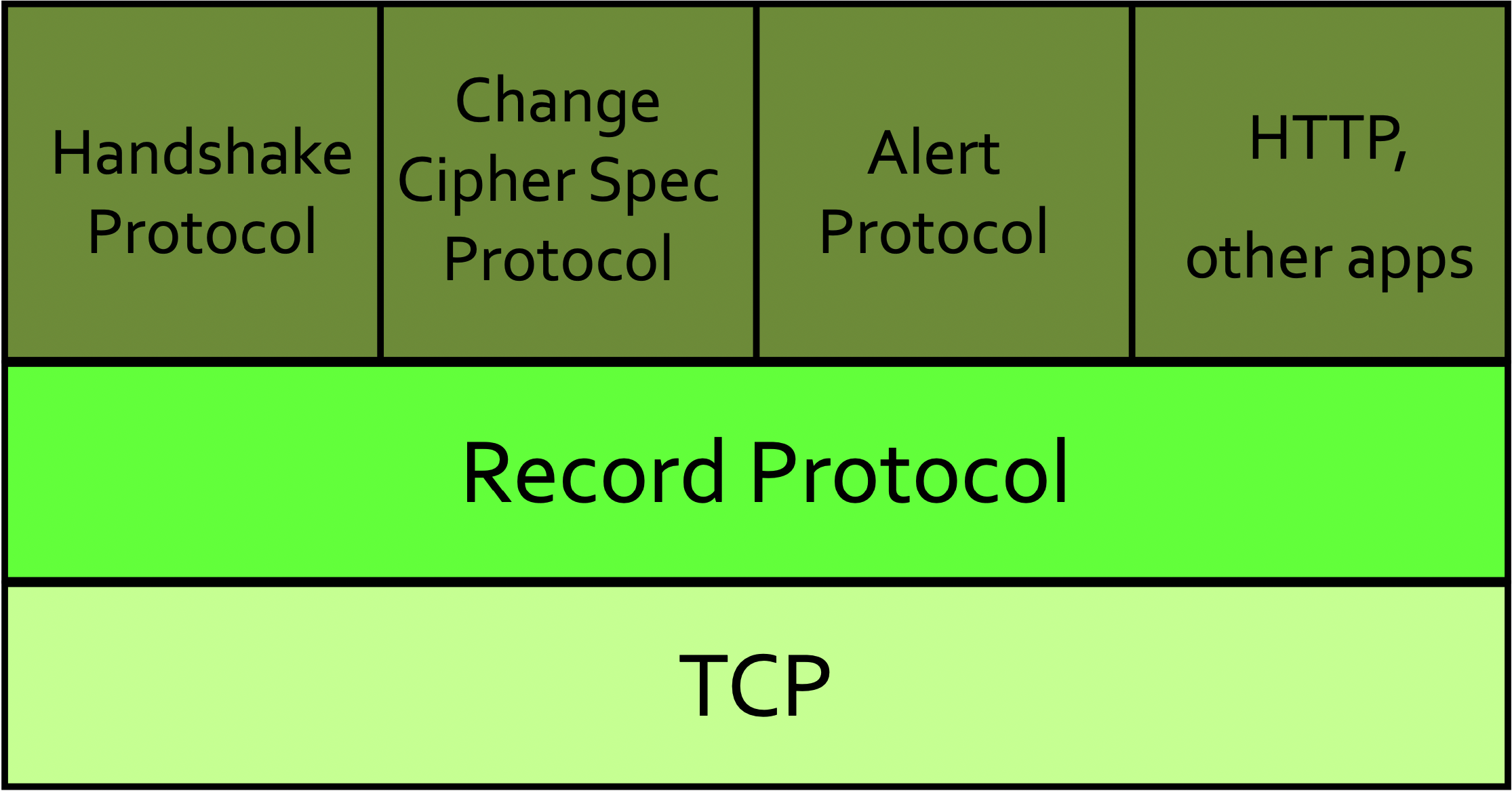

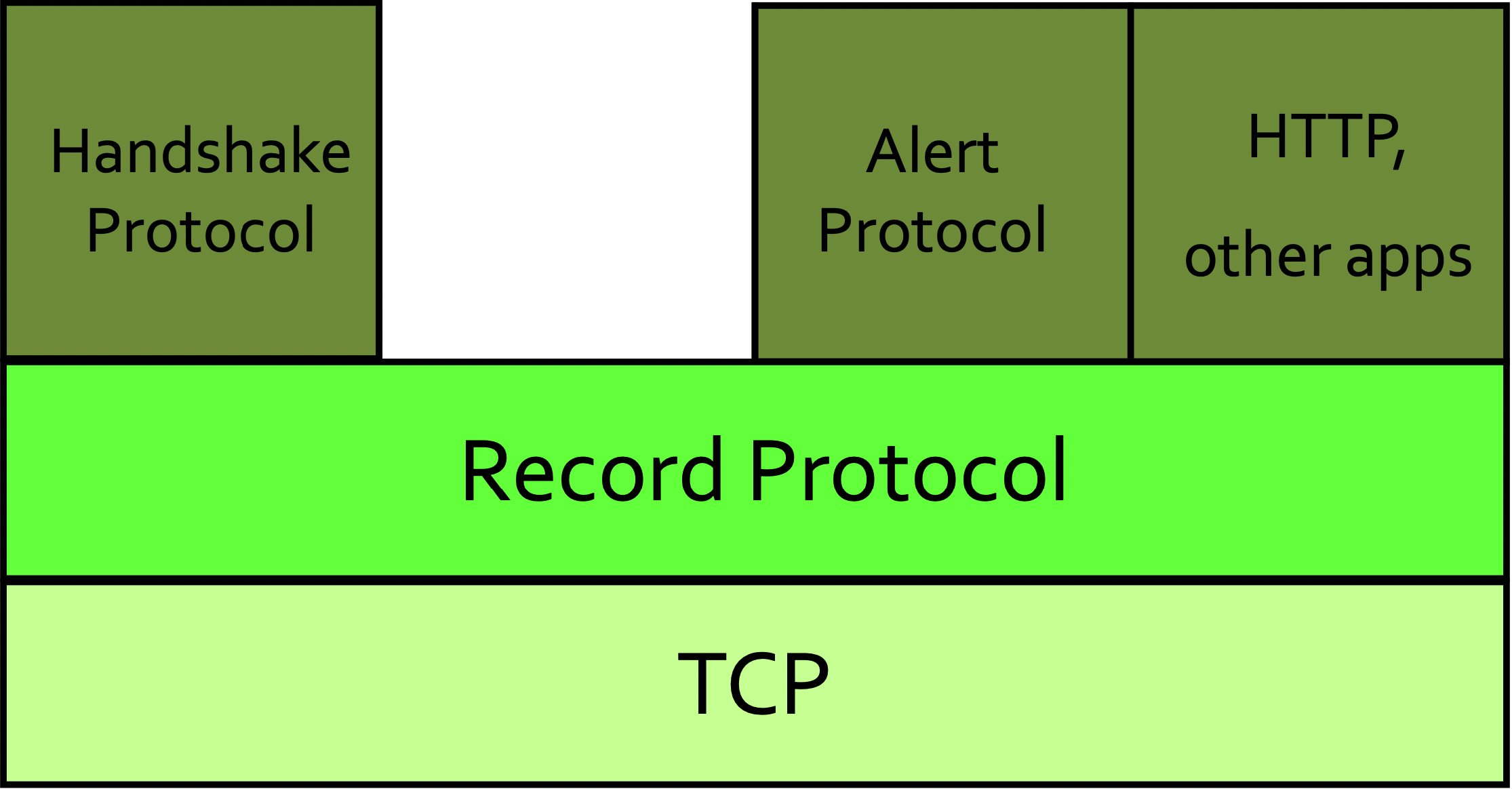

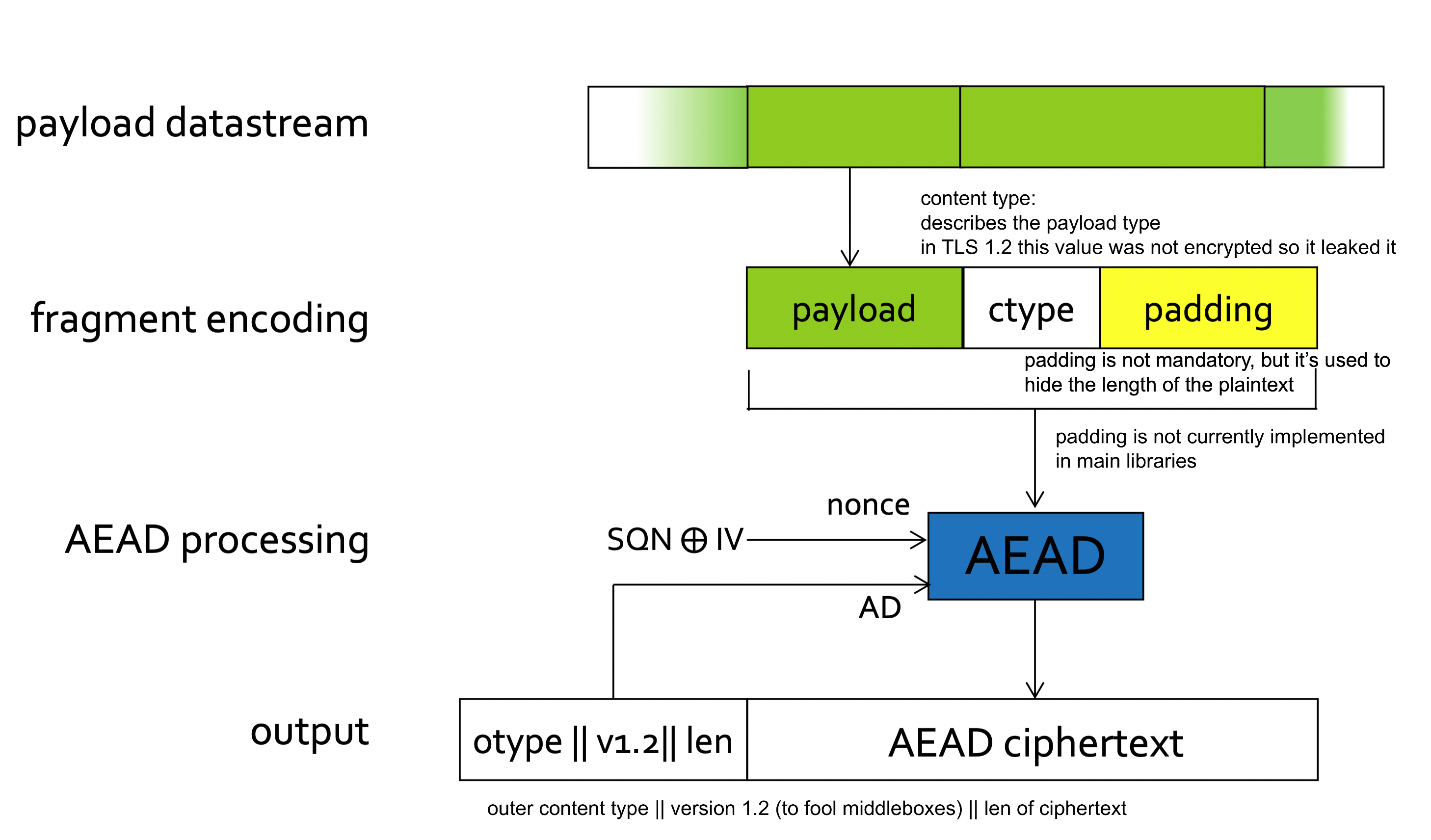

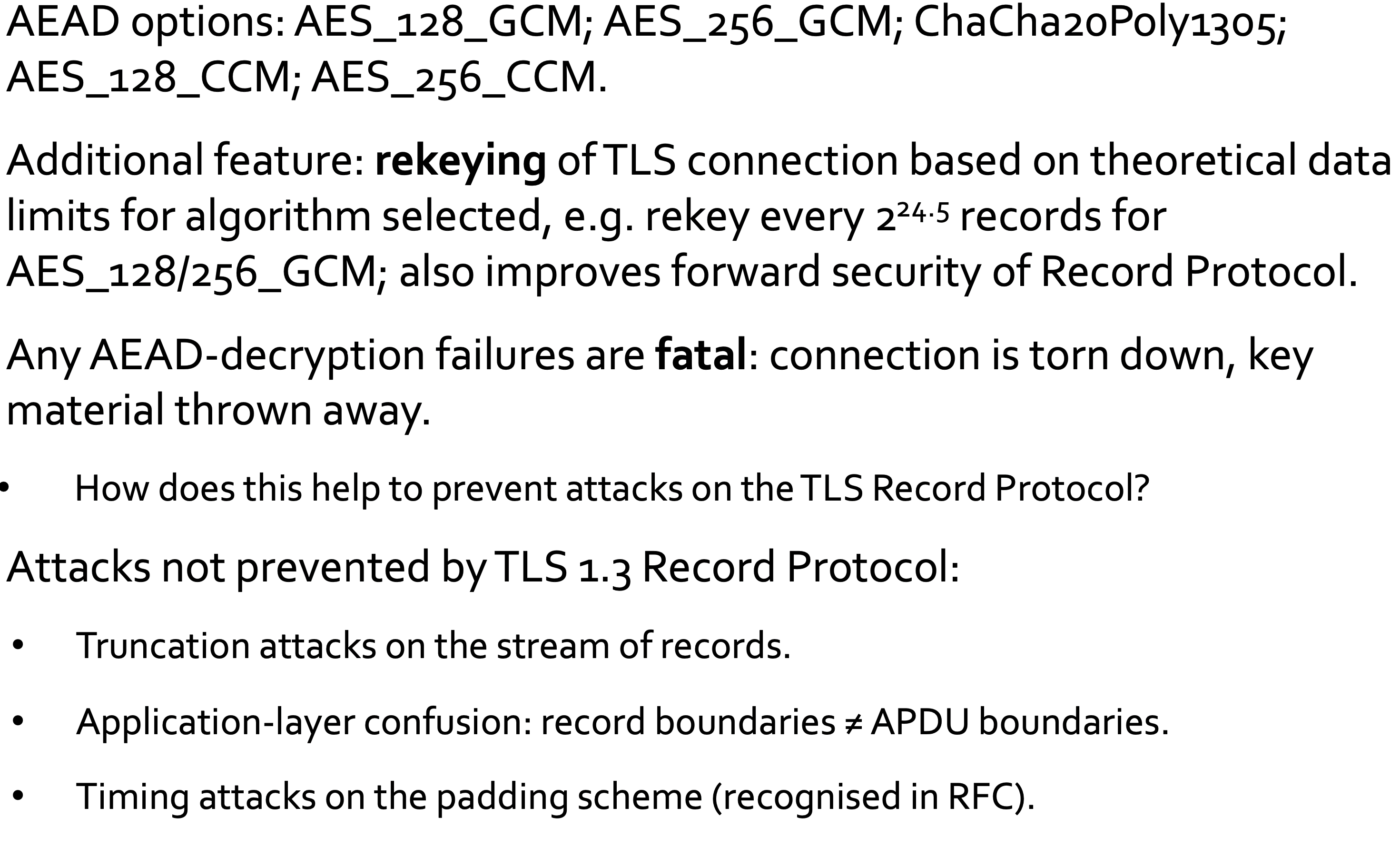

TLS 1.3 Record Protocol

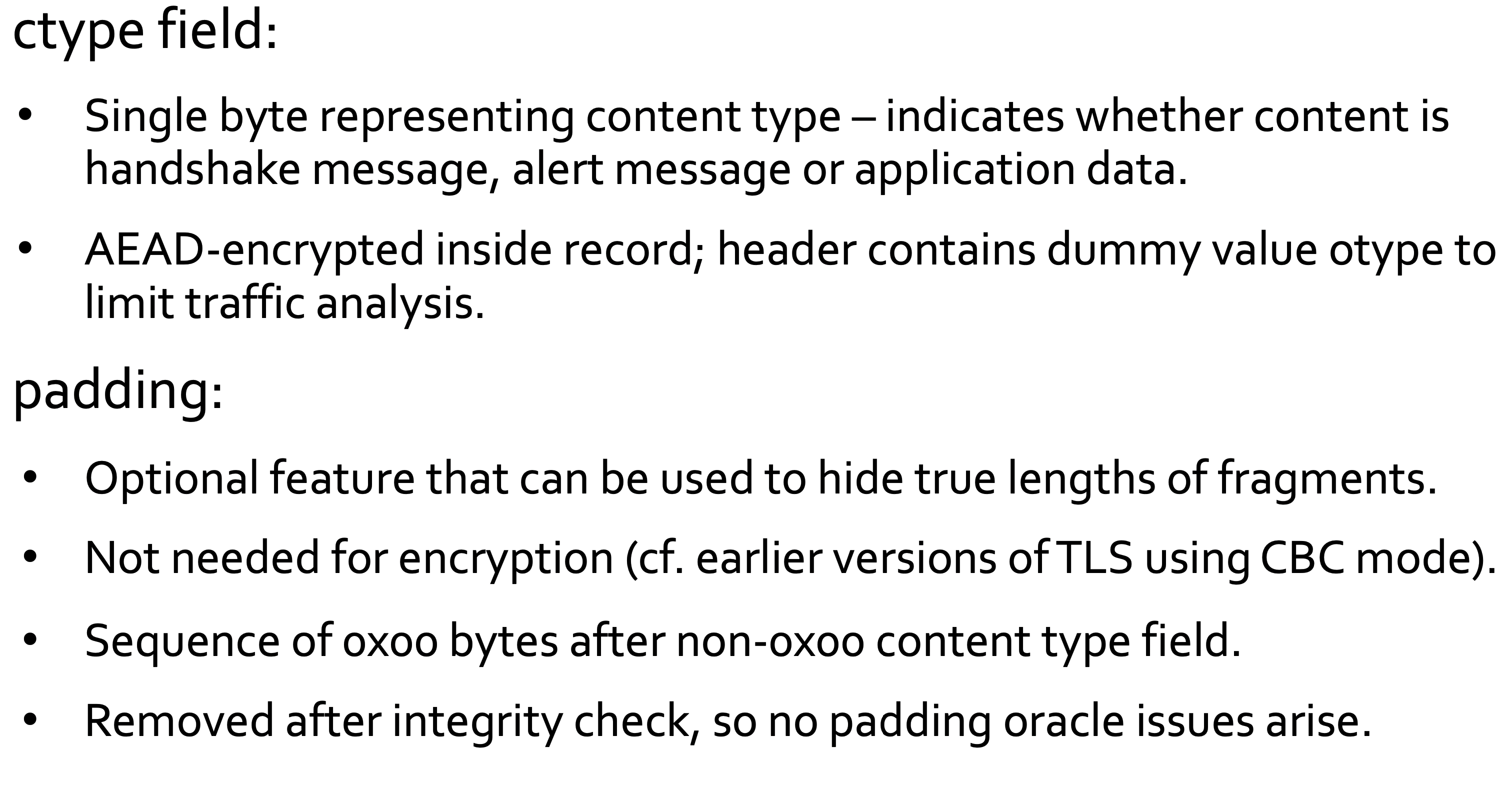

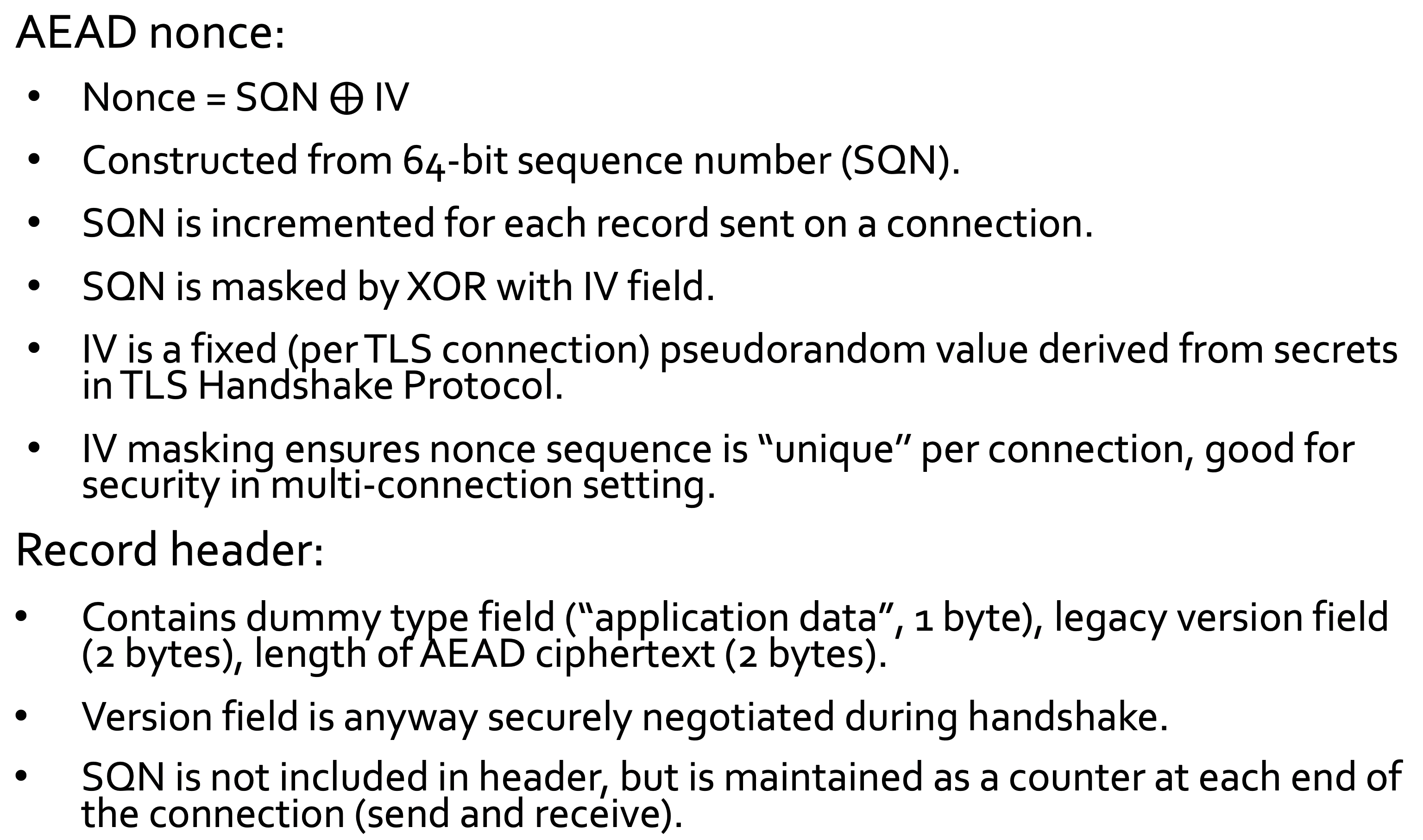

The TLS Record Protocol provides a stream-oriented API for the applications making use of it. This means that TLS may fragment into smaller units or coalesce into larger units any data supplied by the calling application.

Each record is a fragment from a data stream.

Cryptographic protections in the TLS Record Protocol:

- Data origin authentication and integrity for records using a MAC

- Confidentiality for records using a symmetric encryption algorithm.

- Prevention of replay, reordering, deletion of records using per record sequence number protected by the MAC.

- AEAD (Authenticated Encryption with Associated Data) providing encryption and MAC simultaneously

- Prevention of reflection attacks by key separation

- Different symmetric keys in different directions

- However, see Selfie attack.

Record Processing

TLS 1.3 Handshake Protocol

TLS 1.2 and earlier needed 2-RTTs before the client could securely send data (3 including TCP handshake).

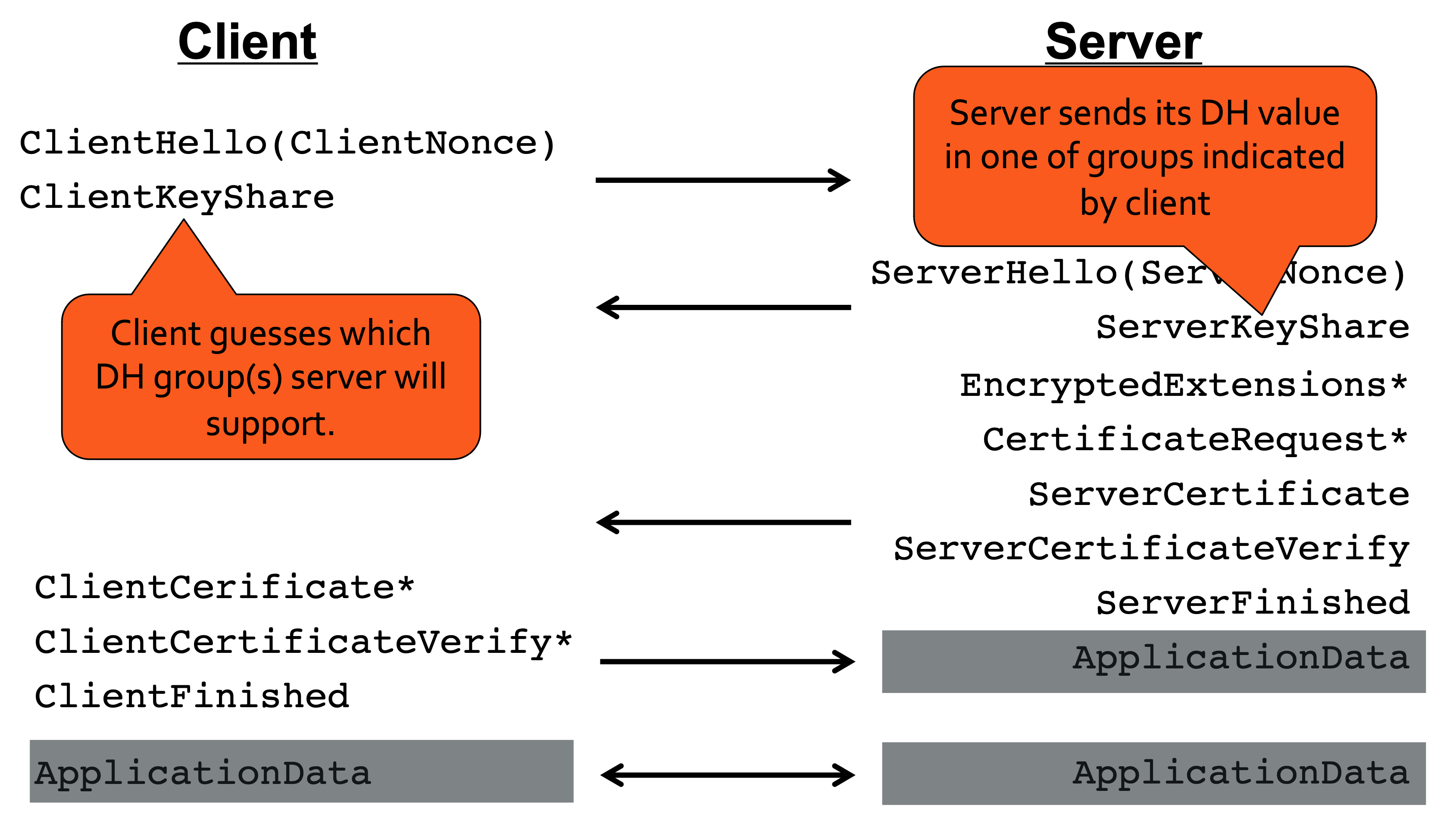

TLS 1.3 achieves a full handshake in 1 RTT, by making the client speculatively send several DH shares in supported groups; then, the server picks one, replies with its share and can already derive Record Protocol keys.

It is also possible to have a 0-RTT handshake when resuming a previously established connection. Client and server keep shared state enabling them to derive a PSK. However, 0-RTT sacrifices replay protection.

- Improved privacy: before TLS 1.3, complete handshake was in the clear (including certificates). Instead, TLS 1.3 derives separate key to protect handshake messages and thus encrypts almost all handshake messages.

- Continuity: remove complex renegotiation protocol, but keep some features (key update + client authentication option). • Interoperability/ease of deployment: make TLS 1.3 ClientHello look like TLS 1.2, so middle-boxes do not block the protocol.

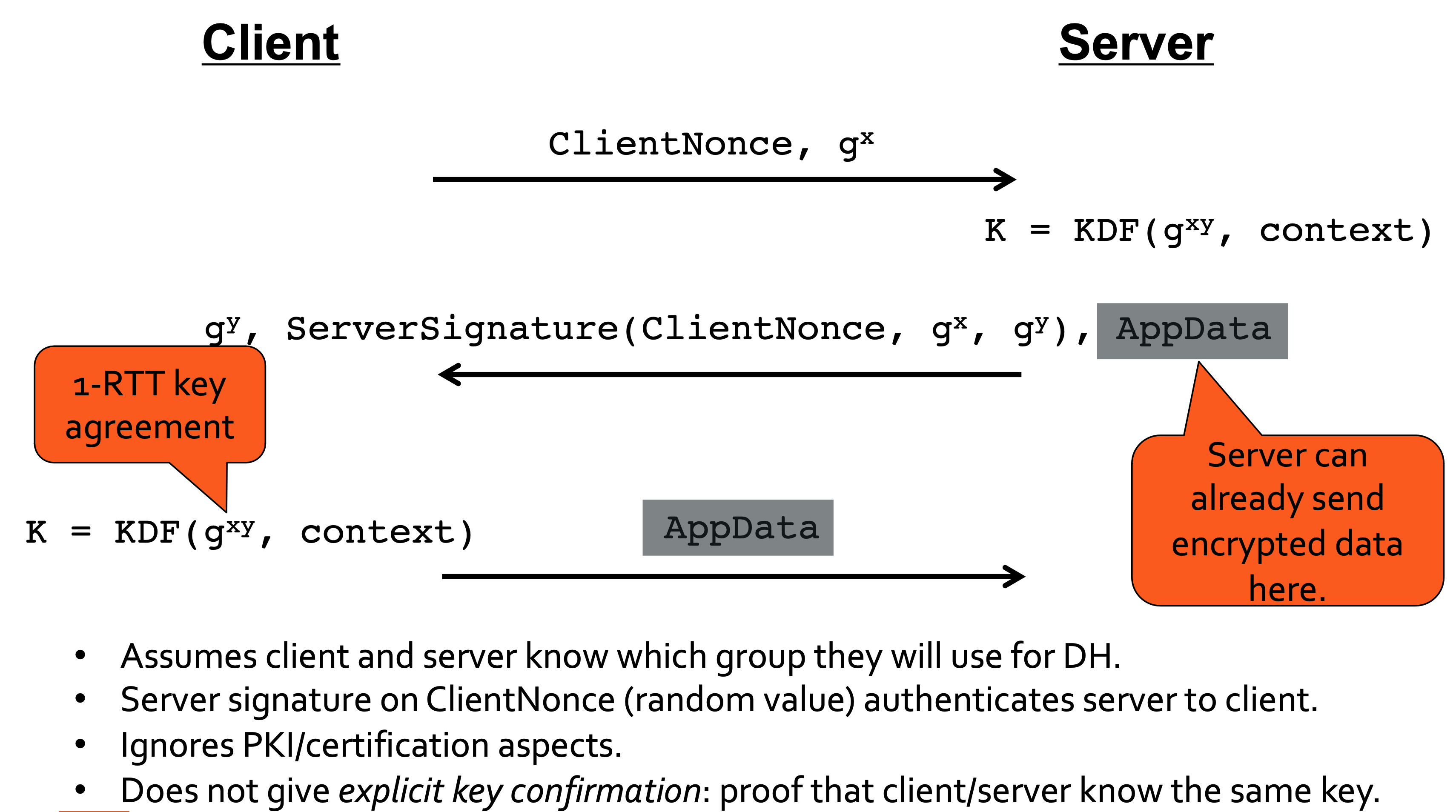

Signed Diffie-Hellman KE

Simplified 1-RTT

- Client includes DH share(s) in its first message, along with ClientHello, anticipating group(s) that server will accept.

- Server responds with single DH share in its ServerKeyShare response.

- If this works, a forward-secure key is established after 1 round trip (1-RTT).

- If server does not like DH group(s) offered by client, it sends a HelloRetryRequest and a group description back to client.

- In this case, the handshake will be 2-RTT.

Limited set of DH and ECDH groups are supported in TLS 1.3: this reduces likelihood of fall-back to 2-RTT, removes problem of client not being able to validate DH parameters that was inherent in TLS 1.2 and earlier, removes complexity from implementations.

Forward security

Because of reliance on Ephemeral DH key exchange, TLS 1.3 Handshake (in this 1-RTT mode) is forward secure. This (informally) means: compromise of all session keys, DH values and signing keys has no impact on the security of earlier sessions.

Use of ephemeral DH also means: if a server’s long-term (signing) key is compromised, then an attacker cannot passively decrypt future sessions. Compare to RSA key transport option in TLS 1.2 and earlier: past and future passive interception using compromised server RSA private key.

Cipher suite and version negotiation

Cipher suites in TLS 1.3 are of the form: TLS_AEAD_HASH

- AEAD: AEAD scheme used in Record Protocol.

- HASH: Hash algorithm used in HKDF/HMAC for key derivation and computation of Finished messages.

There are 5 cipher suites (currently) for TLS 1.3:

- TLS_AES_128_GCM_SHA256

- TLS_AES_256_GCM_SHA384

- TLS_CHACHA20_POLY1305_SHA256

- TLS_AES_128_CCM_SHA256

- TLS_AES_128_CCM_8_SHA256

The client proposes list of cipher suites in ClientHello message. Each cipher suite is encoded as a 2-byte value. The server selects one and returns corresponding 2-byte value in ServerHello.

Values selected are incorporated into signatures and Finished messages as part of transcripts.

Similarly, list of (EC)DHE groups proposed and accepted are included into signatures and Finished messages. Assuming those messages themselves cannot be cryptographically tampered with, then client and server get assurance that both sides have same view of what was proposed and what was accepted.

Similar mechanism to protect TLS version negotiation (but a bit more complicated because of issues in earlier protocol versions).

TLS 1.3 adopts a more complex approach with respect to TLS 1.2, attempting to provide much better key separation and stronger binding of keys to cryptographic context. TLS 1.3 relies heavily on HKDF, a hash-based key derivation function (RFC 5869).

Reliance of the Handshake protocol on randomness

An attacker who can predict a client’s choice of client/server DH private value can passively eavesdrop on all sessions! Those values are produced by client and server PRNG. Nonces in Hello messages may already leak information about state of client or server PRNG. Hence back-doored PRNGs present a serious risk to TLS security: they may allow recovery of future PRNG output from observed output(s).

TLS 1.3 resumption and 0-RTT feature • The future of TLS

Prior versions of TLS had a session resumption feature.

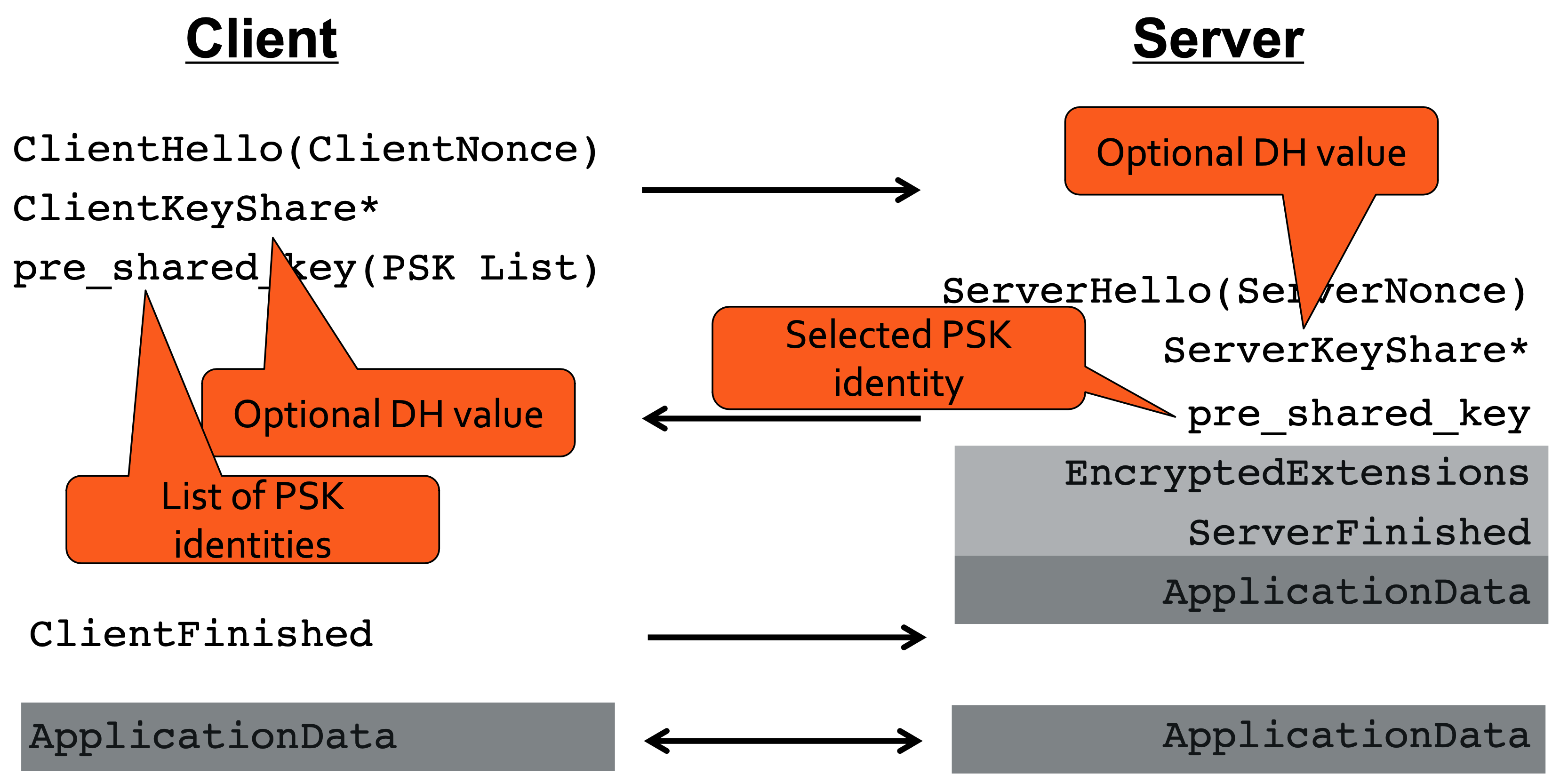

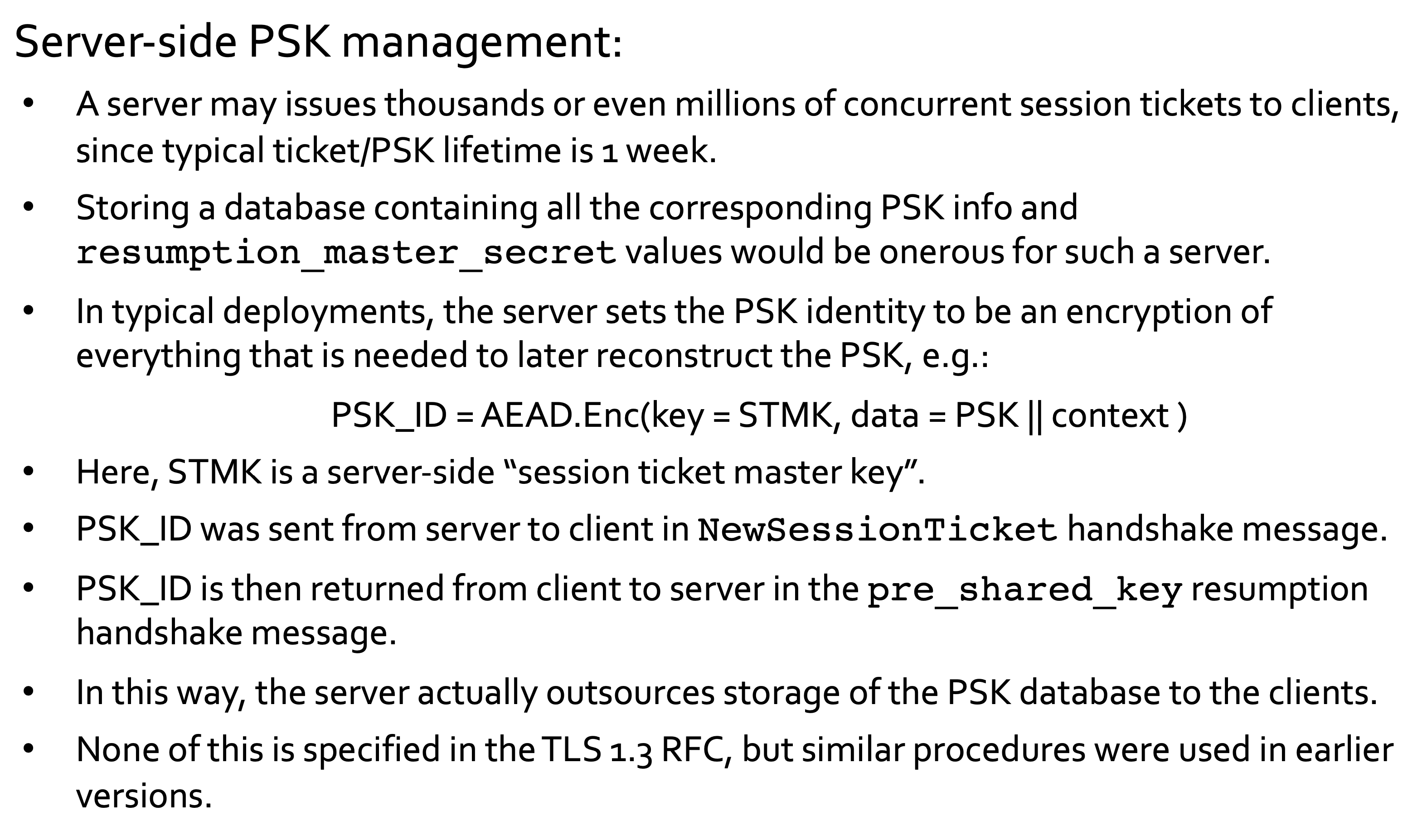

This feature is replicated in TLS 1.3, using the Resumption Handshake. Unified with PSK (Pre-Shared Key) mode for TLS 1.3. Client and server are assumed to have already established PSKs using NewSessionTicket handshake messages (or via out-of-band method in pure PSK mode).

These messages are sent under the protection of existing Record Protocol. Each PSK has an identity – a unique string identifying it at client and server. NewSessionTicket handshake message allows server to deliver a new PSK identity (and other info about the new PSK, including its lifetime and a PSK nonce) to the client. Actual PSK values are derived from the current session’s resumption_master_secret along with PSK nonce:

1

2

PSK = HKDF-Expand-Label(resumption_master_secret, "resumption",

ticket_nonce, Hash.length)

The Resumption Handshake works like a normal handshake, but client sends list of PSK identities in a TLS extension in its first flow, plus optional (EC)DHE value.

Server selects and sends single PSK identity, plus optional (EC)DHE value. PSK identity is just a bit-string; server uses it to look-up the session’s resumption_master_secret (RMS) in a server-side database and then uses RMS to compute the actual PSK.

No server signature; authentication of both parties now based on PSK and Finished messages.

If EC(DHE) values are sent during resumption, then the new session has forward security with respect to the PSK. That is, later compromise of the PSK (or the relevant resumption_master_secret) does not affect security of the newly established session.

Resumption Handshake (simplified)

How servers outsource storage of PSK database to clients