Designing Locks

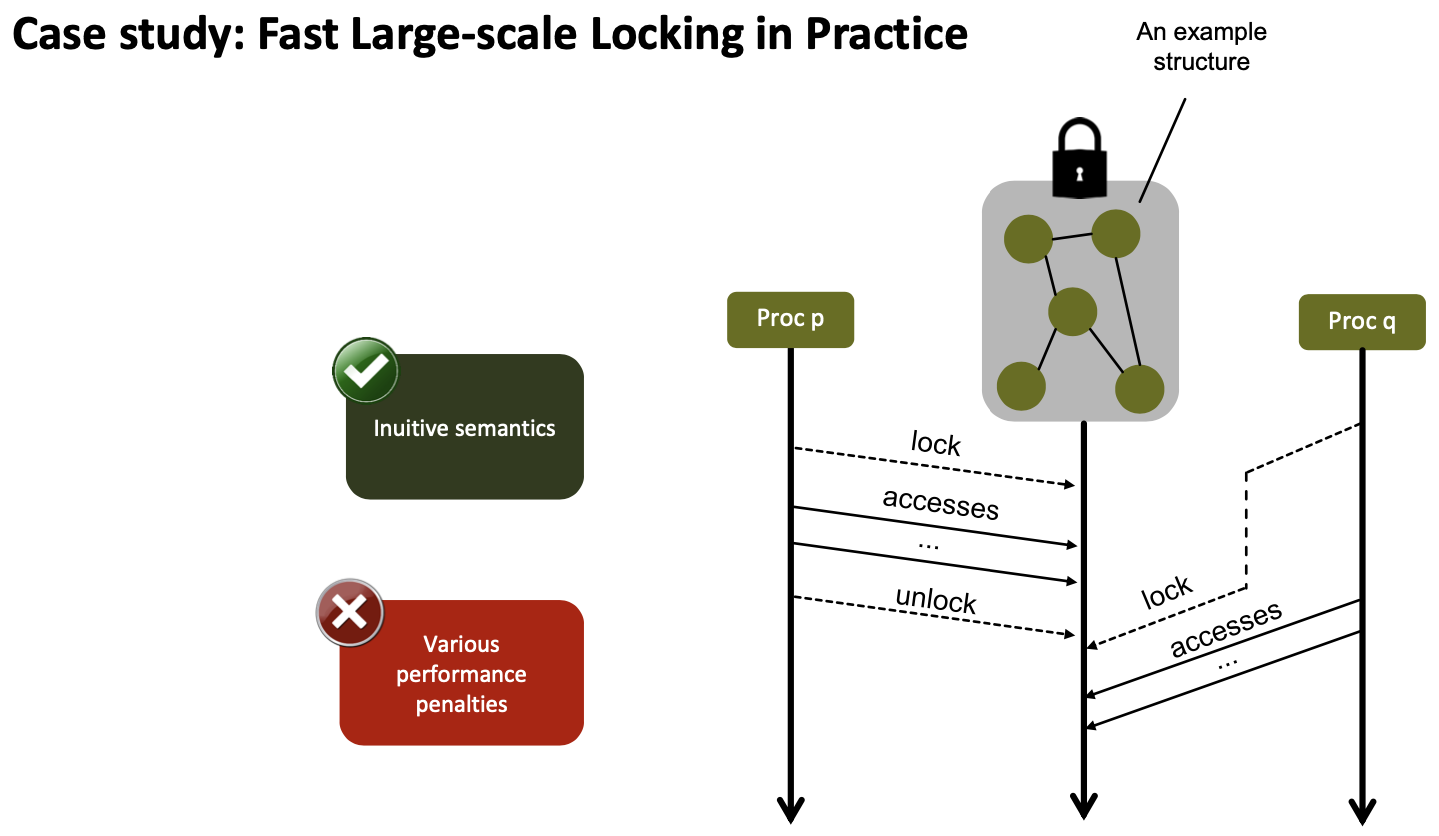

Large-scale Locking and Remote Direct Memory Access

How to lock thousands or processes?

Question: is that useful given that locks provide mutual exclusivity? Mutual exclusivity means serialization increasing Amdahl’s serial fraction limiting scalability, right?

Locks: Challenges

- We need intra- and inter-node topology-awareness

- We need to cover arbitrary topologies

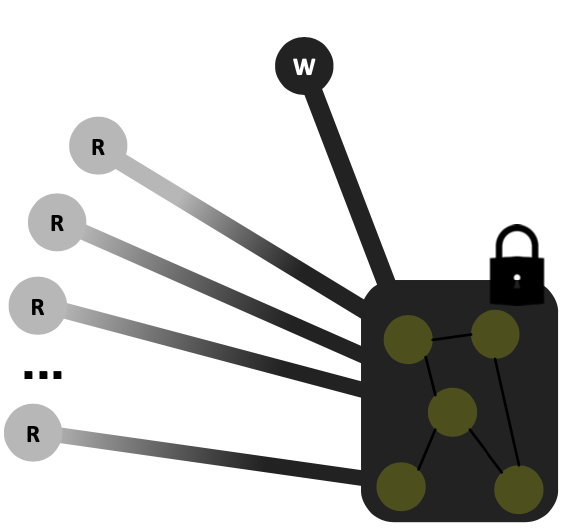

- We need to distinguish between readers and writers

- We need flexible performance for both types of processes

Designing Locks

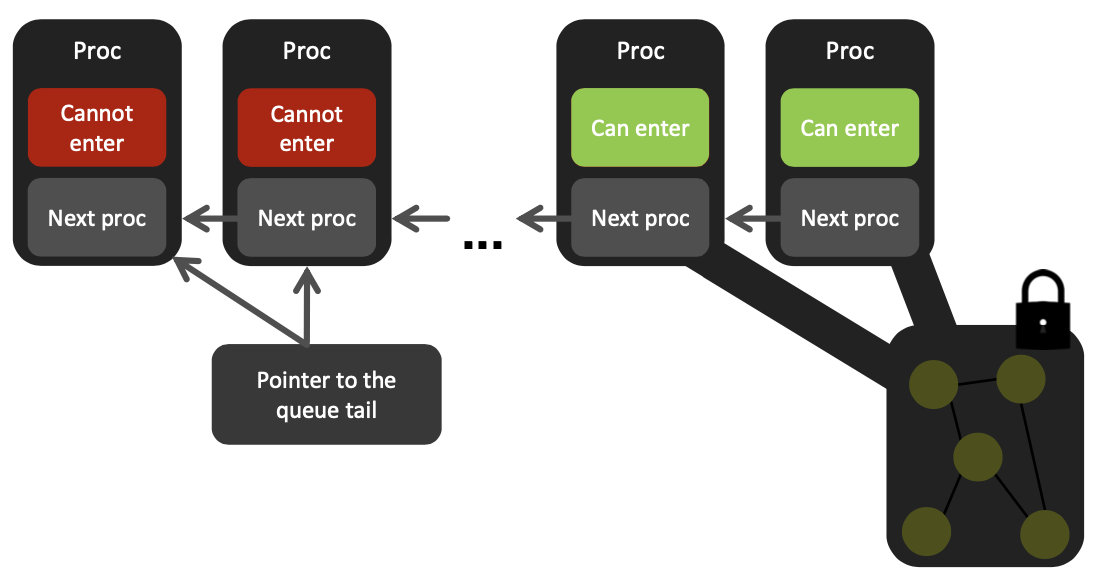

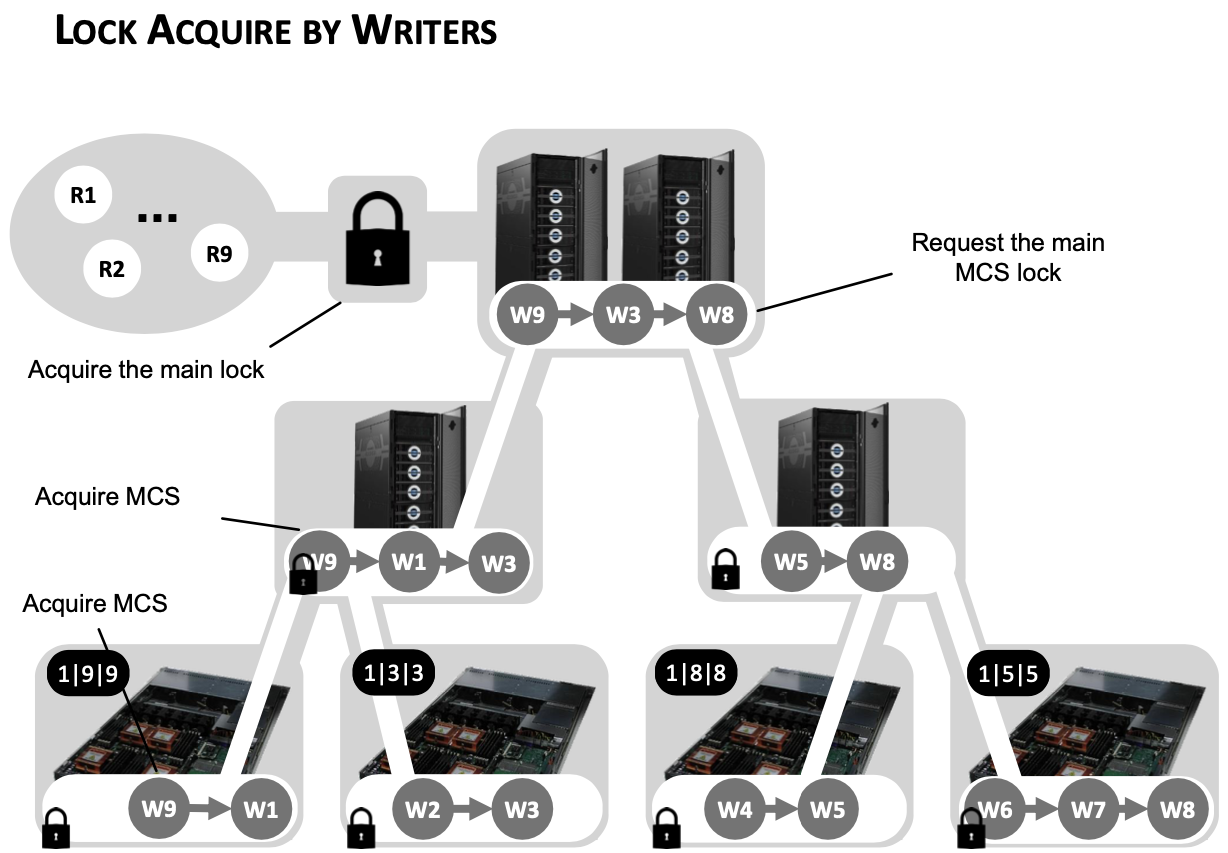

Ingredient 1 - MCS Locks

Ingredient 2 - Reader-Writer Locks

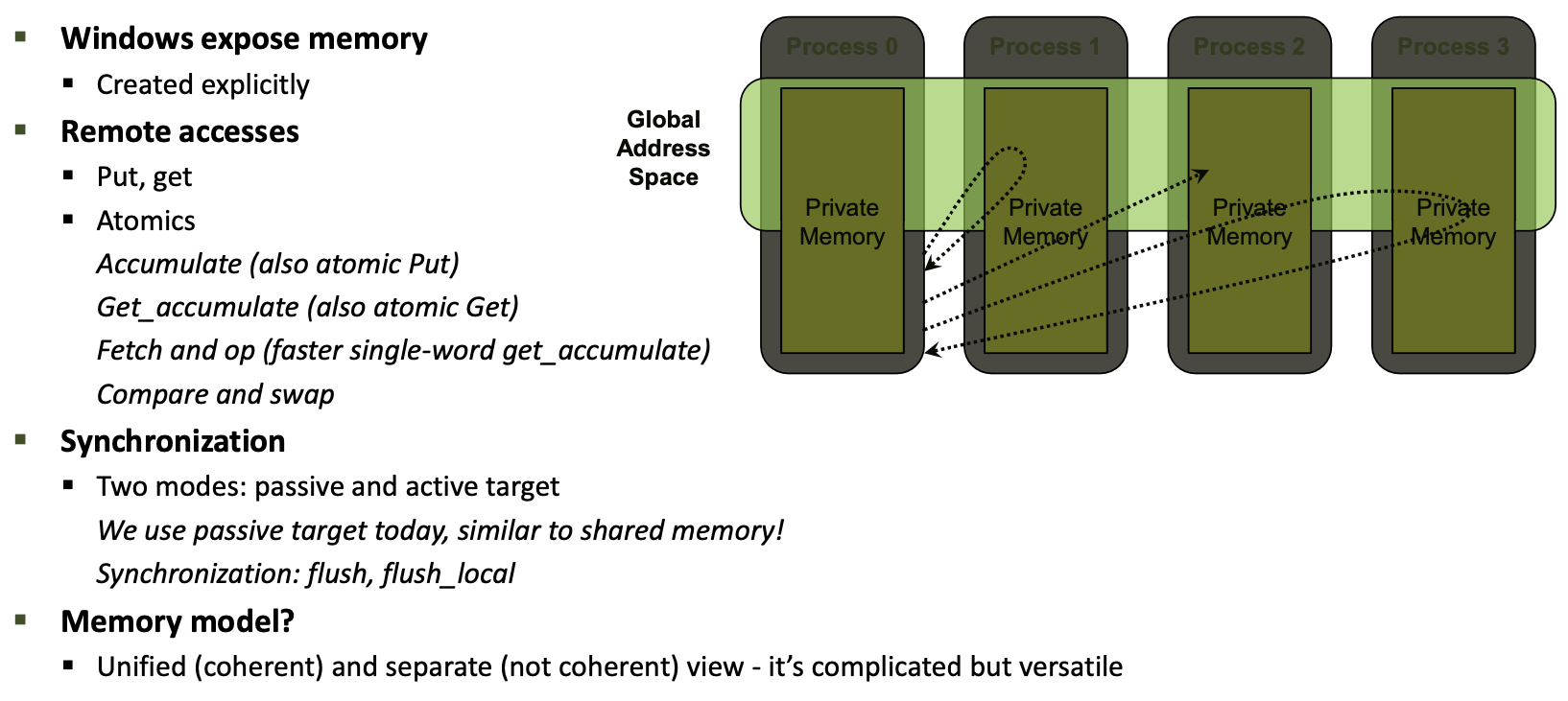

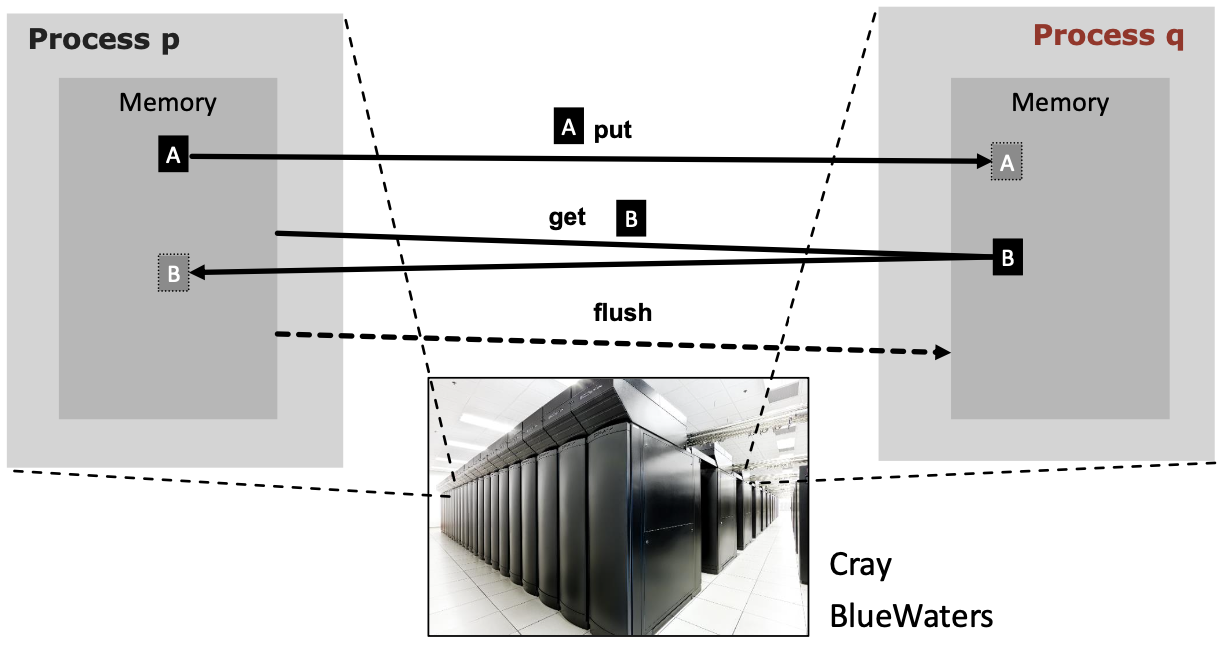

Remote Memory Access Programming

RDMA support implemented in hardware in NICs in the majority of HPC networks

RDMA support implemented in hardware in NICs in the majority of HPC networks

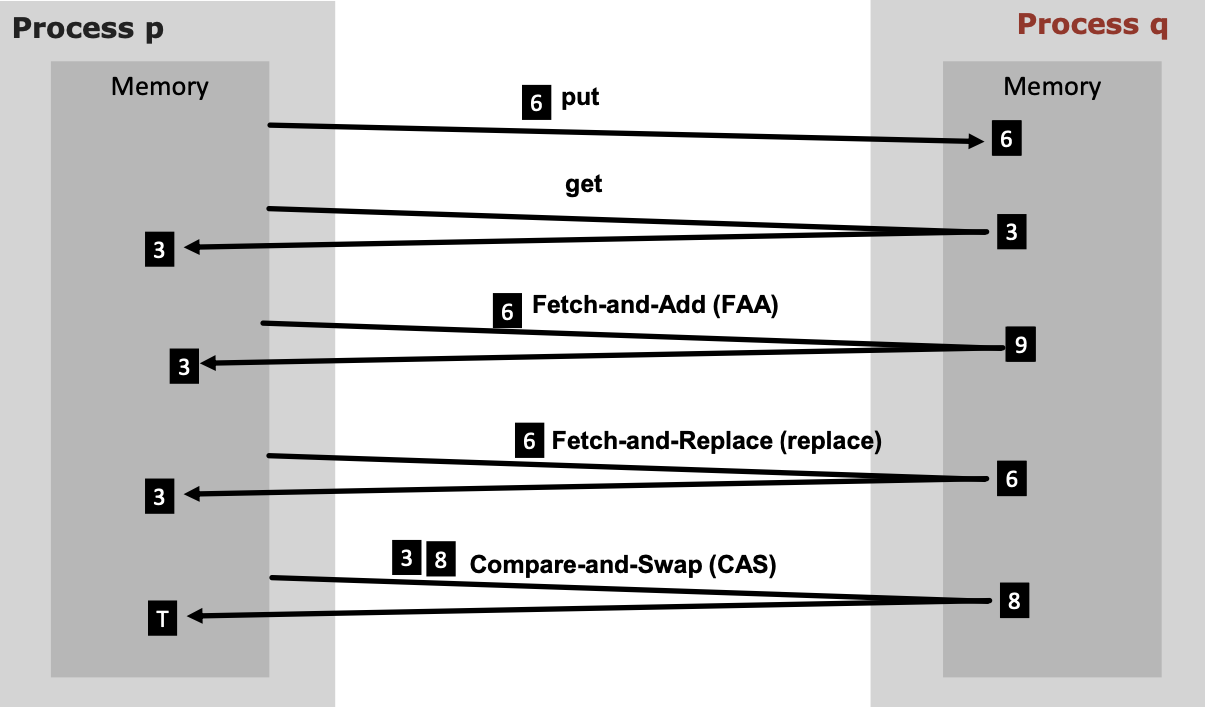

RMA-RW - Required Operations

Recitation recap: MPI RMA

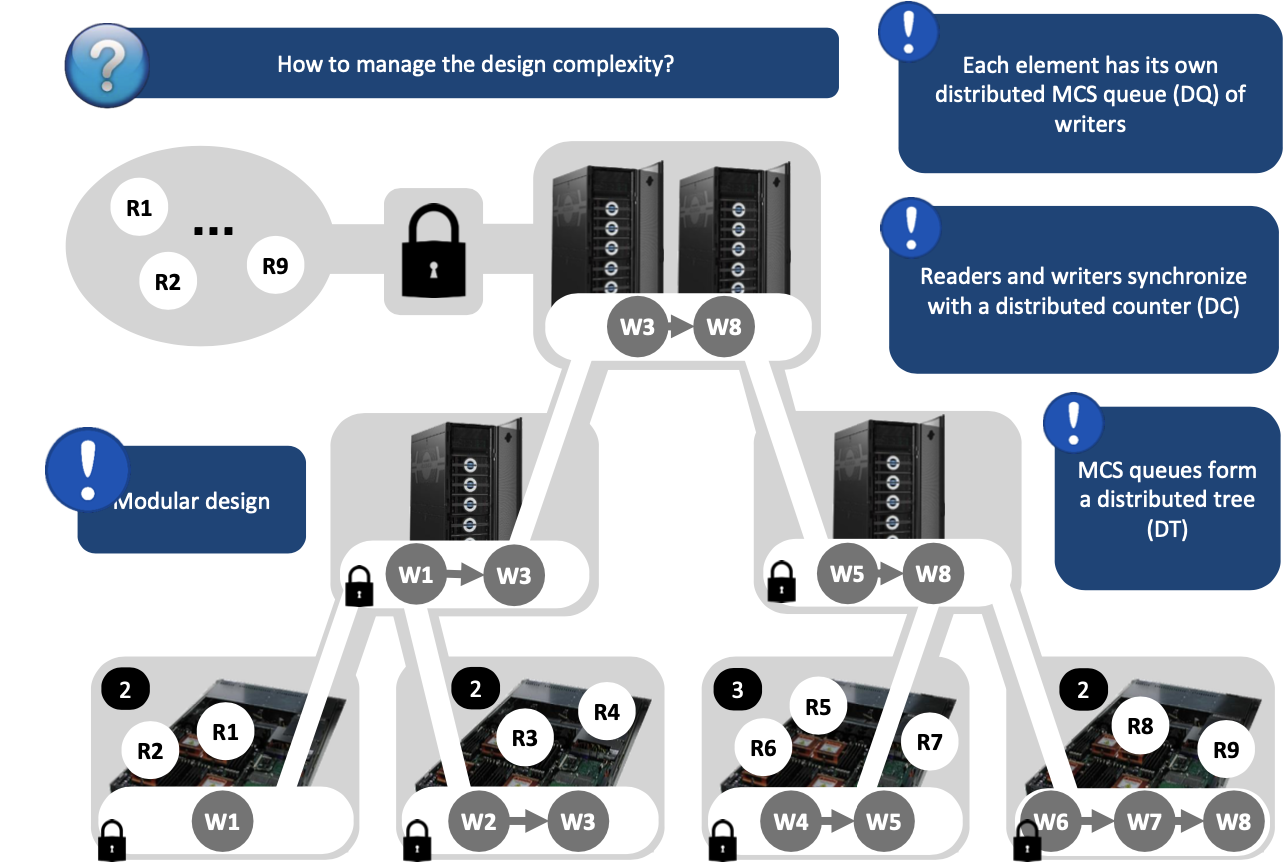

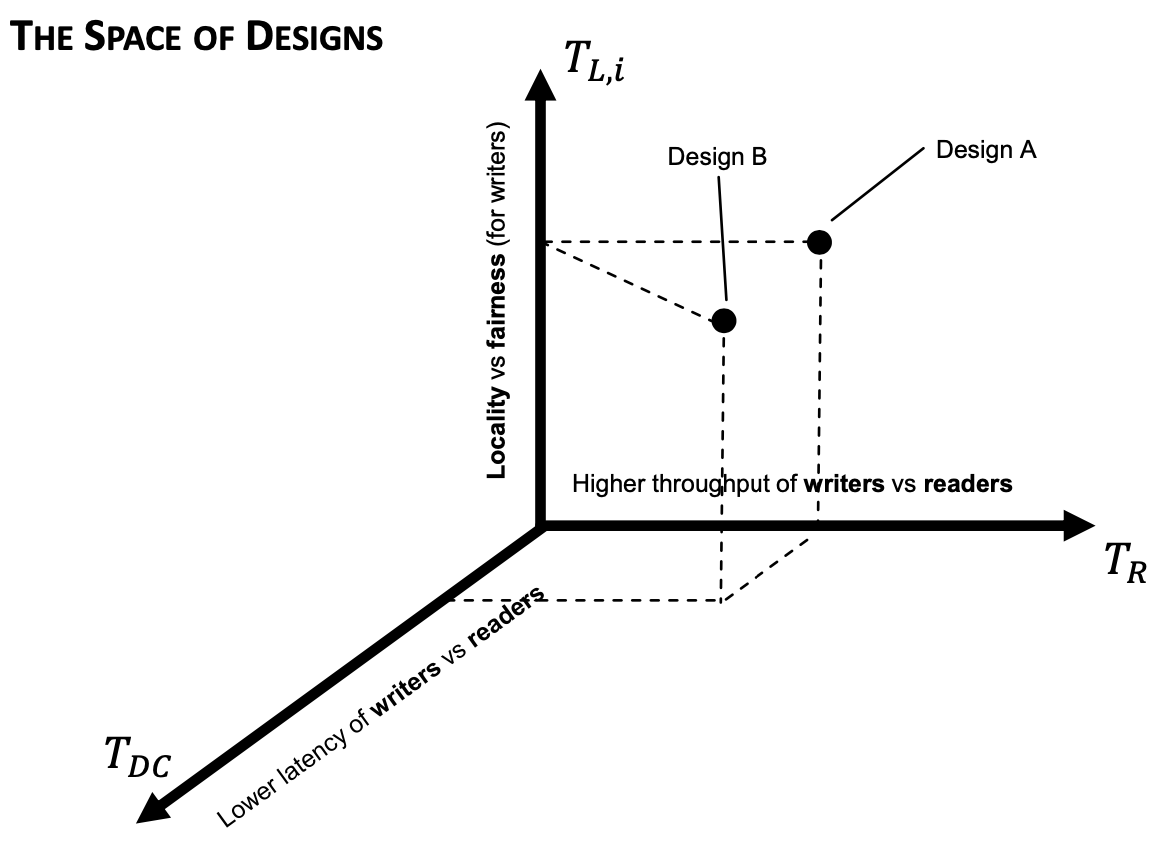

How to ensure tunable performance? Each DQ: fairness vs throughput of writers DC: a parameter for the latency of readers vs writers A tradeoff parameter for every structure DT: a parameter for the throughput of readers vs writers

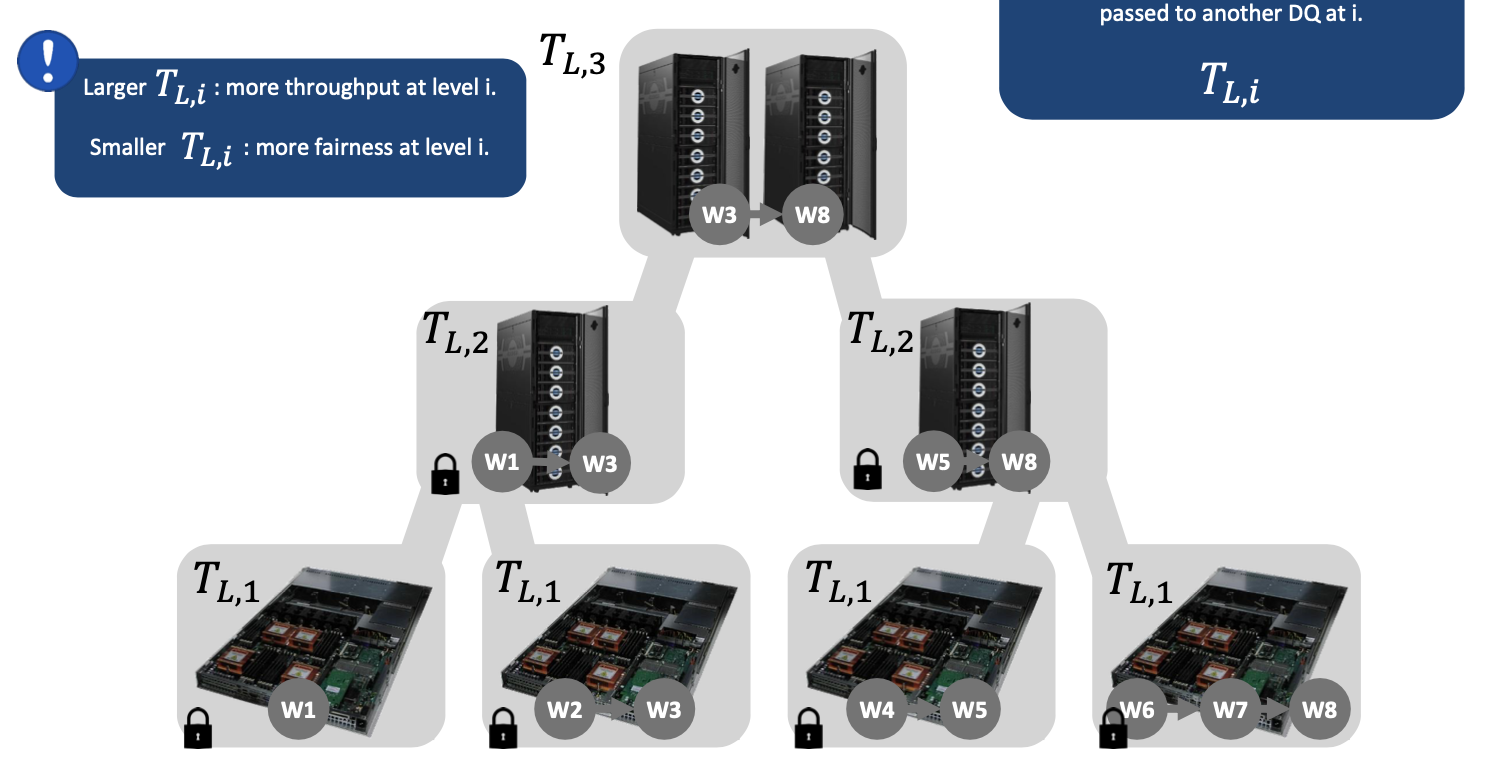

DISTRIBUTED MCS QUEUES (DQS) Throughput vs Fairness

Each DQ: The maximum number of lock passings within a DQ at level i, before it is passed to another DQ at i.

\[T_{𝐿,i}\]Larger $T_{𝐿,i}$: more throughput at level i.

Smaller $T_{𝐿,i}$: more fairness at level i.

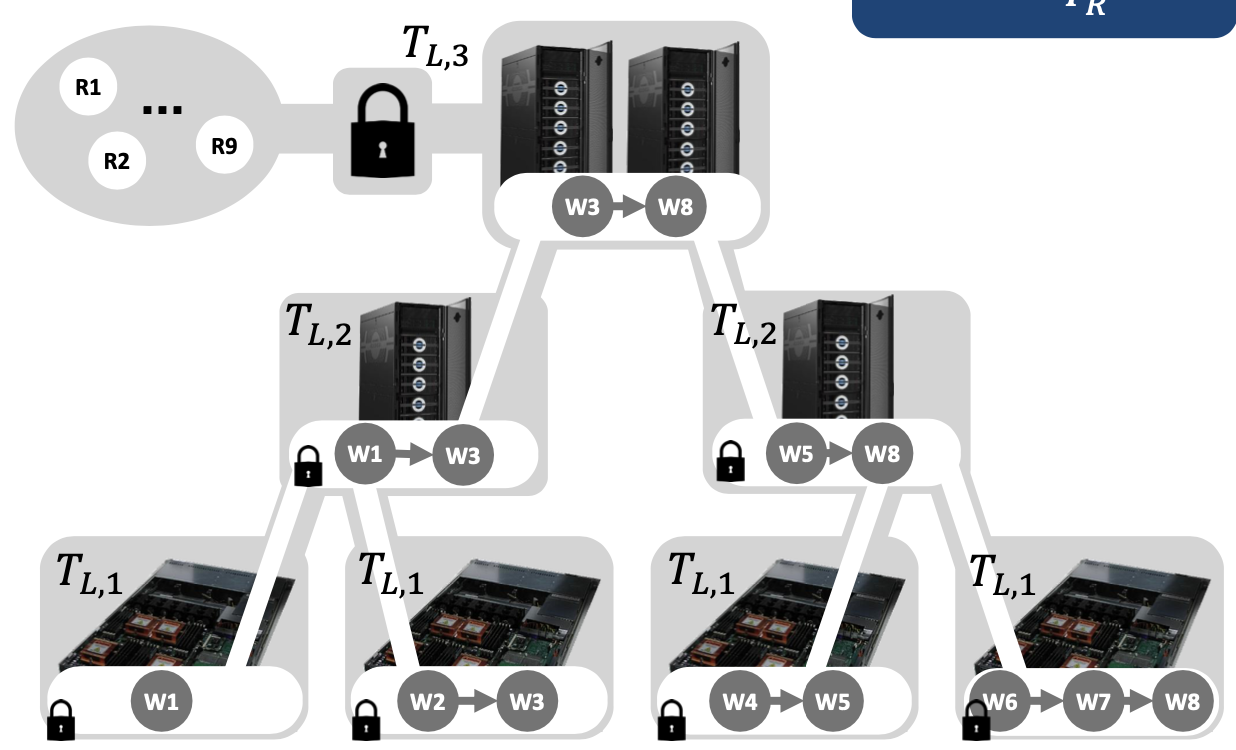

DISTRIBUTED TREE OF QUEUES (DT) Throughput of readers vs writers

DT: The maximum number of consecutive lock passings within readers ($T_R$). a.k.a.: the number of readers you admit before checking for a writer.

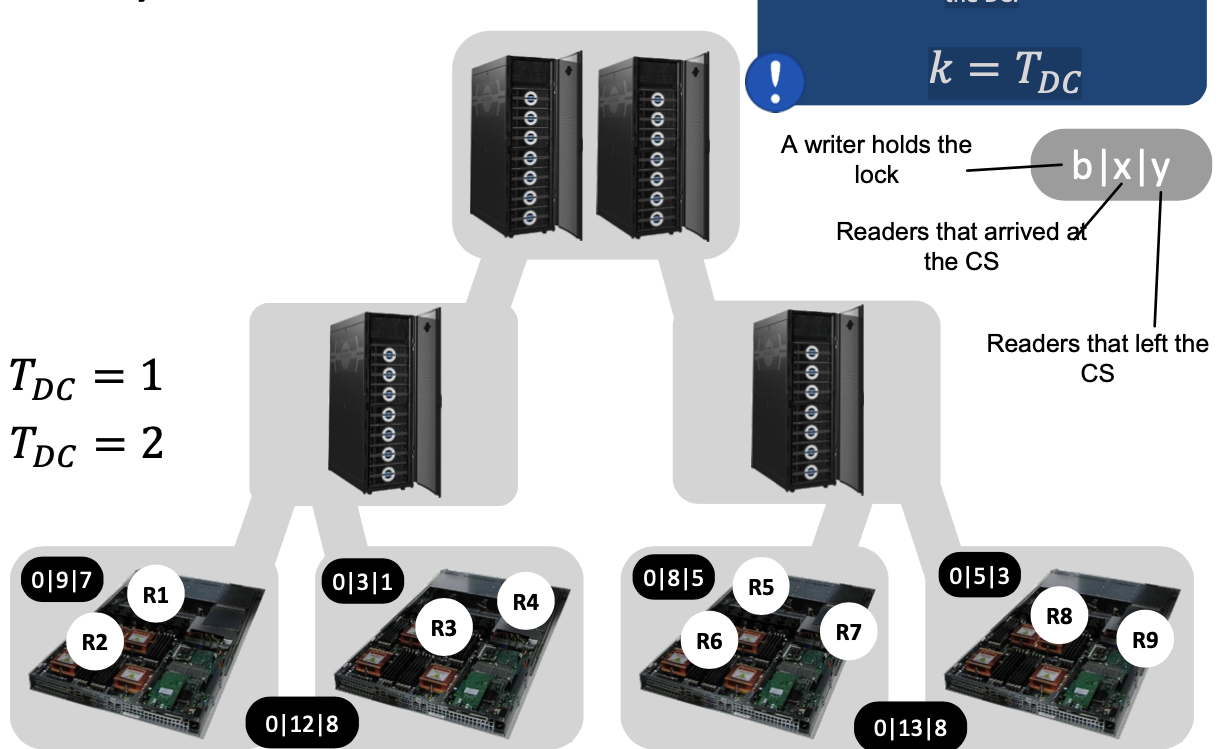

DISTRIBUTED COUNTER (DC) Latency of readers vs writers

DC: every kth compute node hosts a partial counter, all of which constitute the DC. \(k = T_{DC}\)

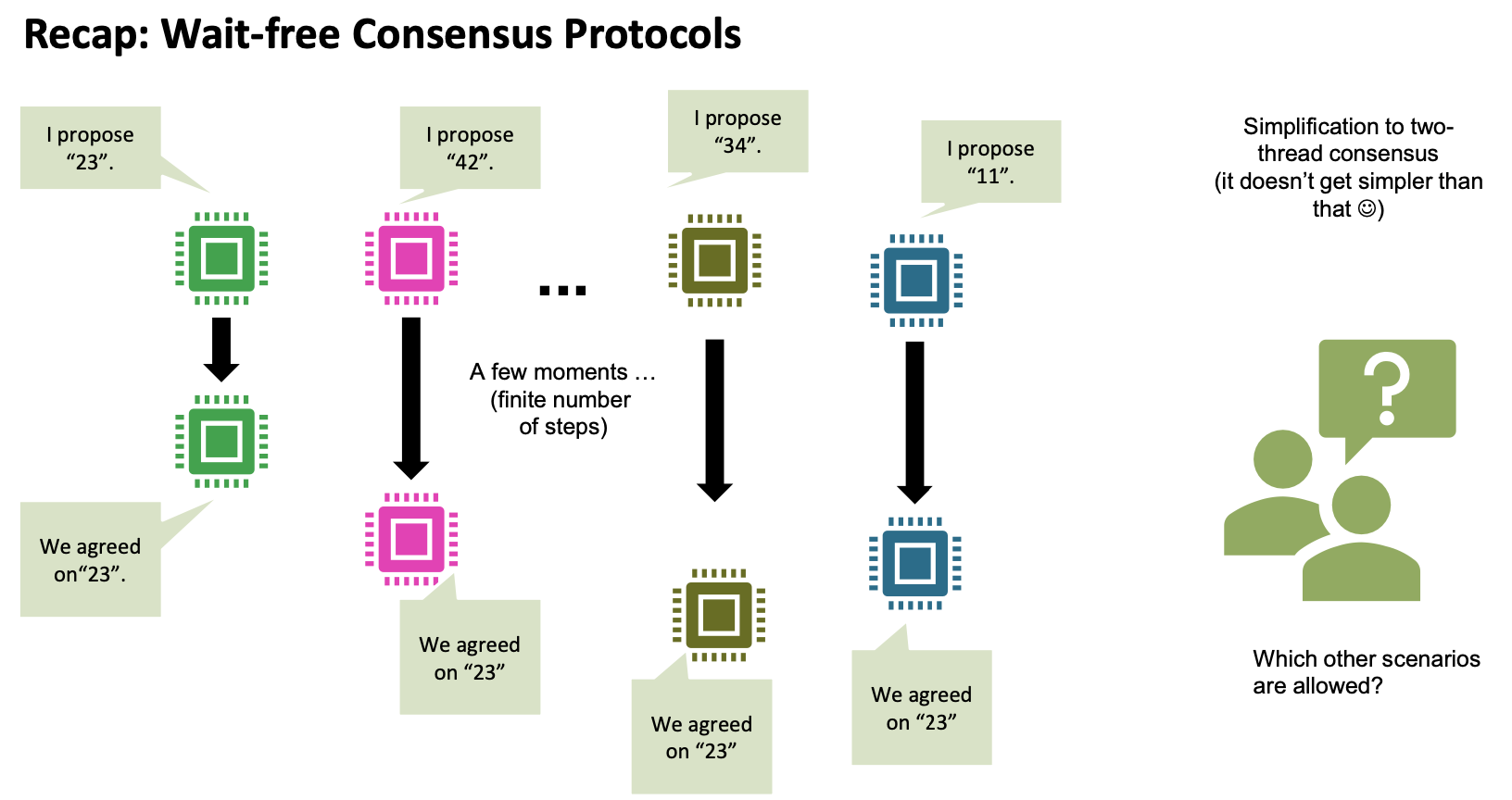

Reminder: lock-free vs. wait-free

A locked method

- May deadlock (methods may never finish) A lock-free method

- Guarantees that infinitely often some method call finishes in a finite number of steps

A wait-free method

- Guarantees that each method call finishes in a finite number of steps (implies lock-free)

- Strongest guarantee – always nice to have, may be expensive (often in terms of memory) – crucial for critical systems

Recurring theme: helping (faster threads help slower threads, e.g., wait-free queues)

Synchronization instructions are not equally powerful!

- e.g., CAS, FADD, Swap, atomic r/w, transactional memory, etc. – which one to use or implement?

Indeed, they form an infinite hierarchy; no instruction (primitive) in level $x$ can be used for lock-/wait-free implementations of primitives in level $z>x$.

If a program is lock-free, it basically means that at least one of its threads is guaranteed to make progress over an arbitrary period of time. If a program deadlocks, none of its threads (and therefore the program as a whole) cannot make progress - we can say it’s not lock-free. Since lock-free programs are guaranteed to make progress, they are guaranteed to complete (assuming finite execution without exceptions).

Wait-free is a stronger condition which means that every thread is guaranteed to make progress over an arbitrary period of time, regardless of the timing/ordering of thread execution; and so we can say that the threads finish independently. All wait-free programs are lock-free.

Concept: Consensus Number

Each level of the hierarchy has a “consensus number” assigned.

- It’s the maximum number of threads for which primitives in level x can solve the consensus problem The consensus problem:

- Has single function: decide(v)

- Each thread calls it at most once, the function returns a value that meets two conditions:

- consistency: all threads get the same value

- validity: the value is some thread’s input

- Simplification: binary consensus (inputs in {0,1})

It’s one of the simplest representatives of wait-free algorithms! Still shows all the issues

Understanding Consensus

Can a particular class solve n-thread consensus wait-free?

- A class C solves n-thread consensus if there exists a consensus protocol using any number of objects of class C and any number of atomic registers

- The protocol must be wait-free (bounded number of steps for each thread)

- The consensus number of a class C is the largest n for which that class solves n-thread consensus (may be infinite)

- Assume we have a class D whose objects can be constructed from objects out of class C. If class C has consensus number n, what does class D have?

Atomic Registers

Theorem [Herlihy’91]: Atomic registers have consensus number one

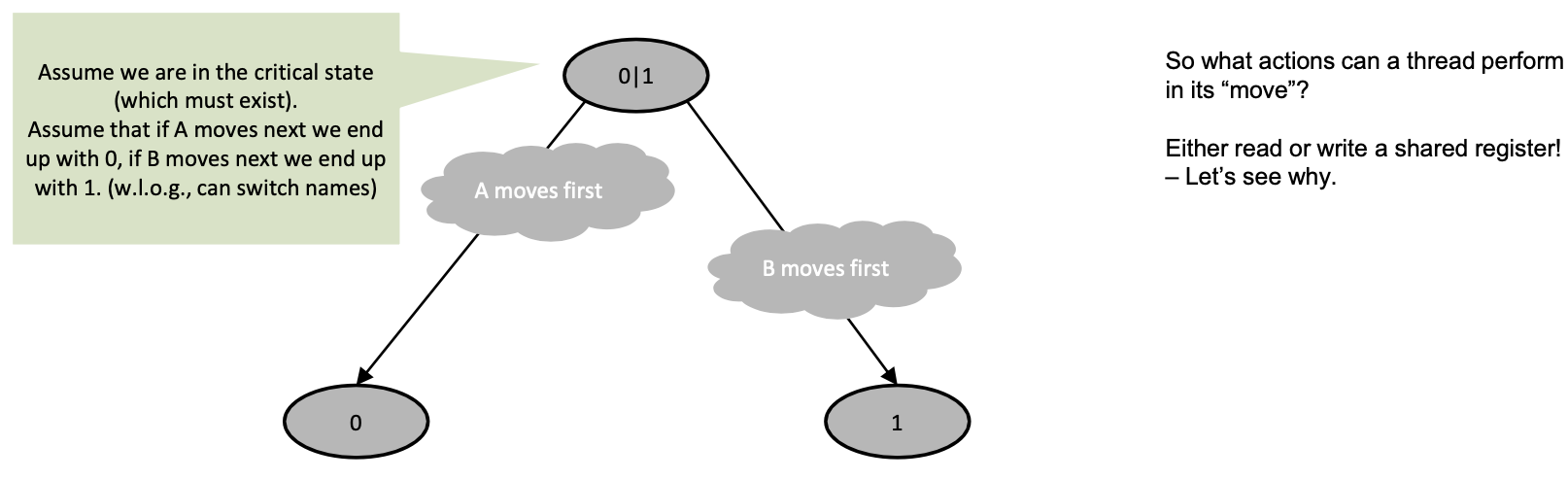

- i.e., they cannot be used to solve even two-thread consensus! Really? Proof outline:

- Assume arbitrary consensus protocol, thread A, B

- Run until it reaches critical state where next action determines outcome (show that it must have a critical state first)

- Show all options using atomic registers and show that they cannot be used to determine one outcome for all possible executions!

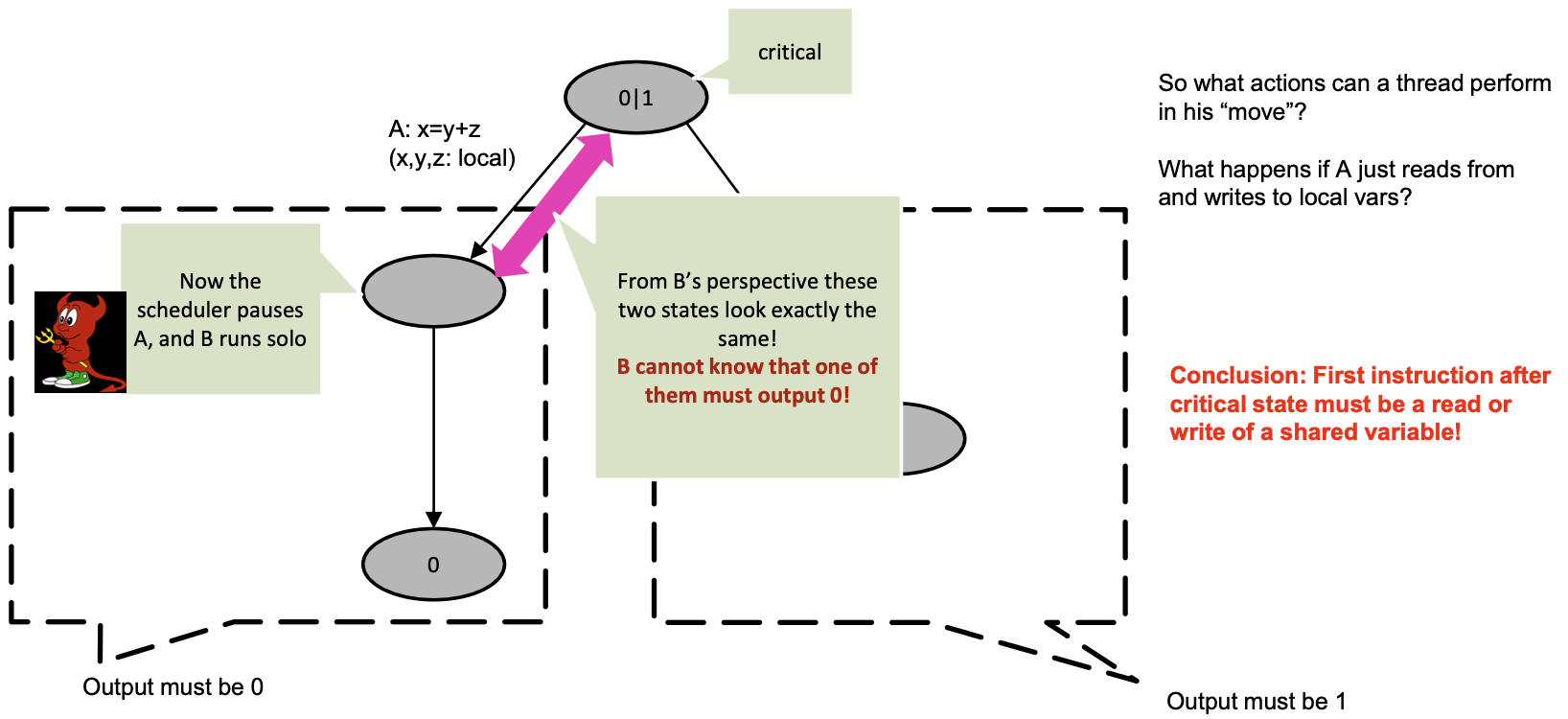

- Any thread reads (other thread runs solo until end)

- Threads write to different registers (order doesn’t matter)

- Threads write to same register (solo thread can start after each write)

Corollary: It is impossible to construct a wait-free implementation of any object with consensus number of >1 using atomic registers

- → We need hardware atomics or Transactional Memory!

Consensus result needs to be valid: a.k.a. return one of the numbers proposed by some thread.

Consensus needs to be wait-free: All threads finish after a finite number of steps, independently of other threads.

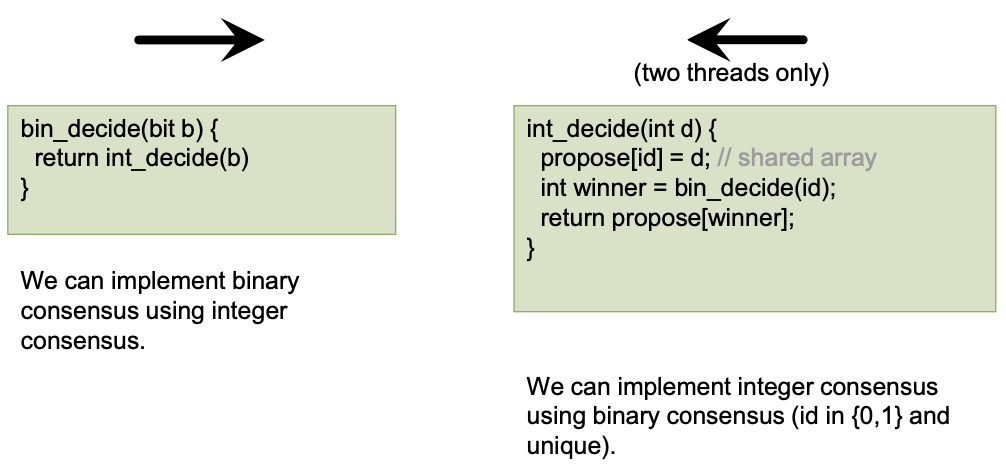

Simplification: Binary Consensus

Instead of proposing an integer, every thread now proposes either 0 or 1

- Equivalent to “normal” consensus for two threads

- How can we proof this?

- If we have int_decide(int) as primitive, we can implement bin_decide(bit) and vice-versa

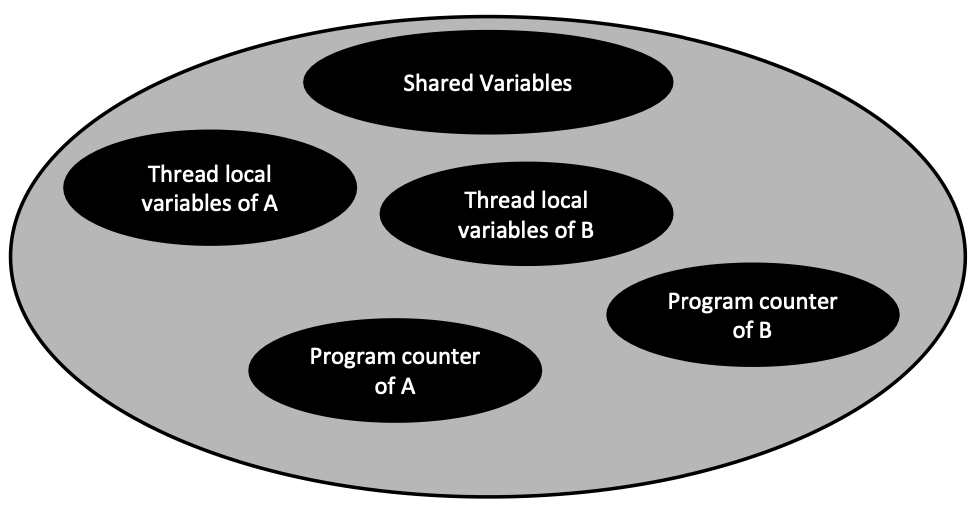

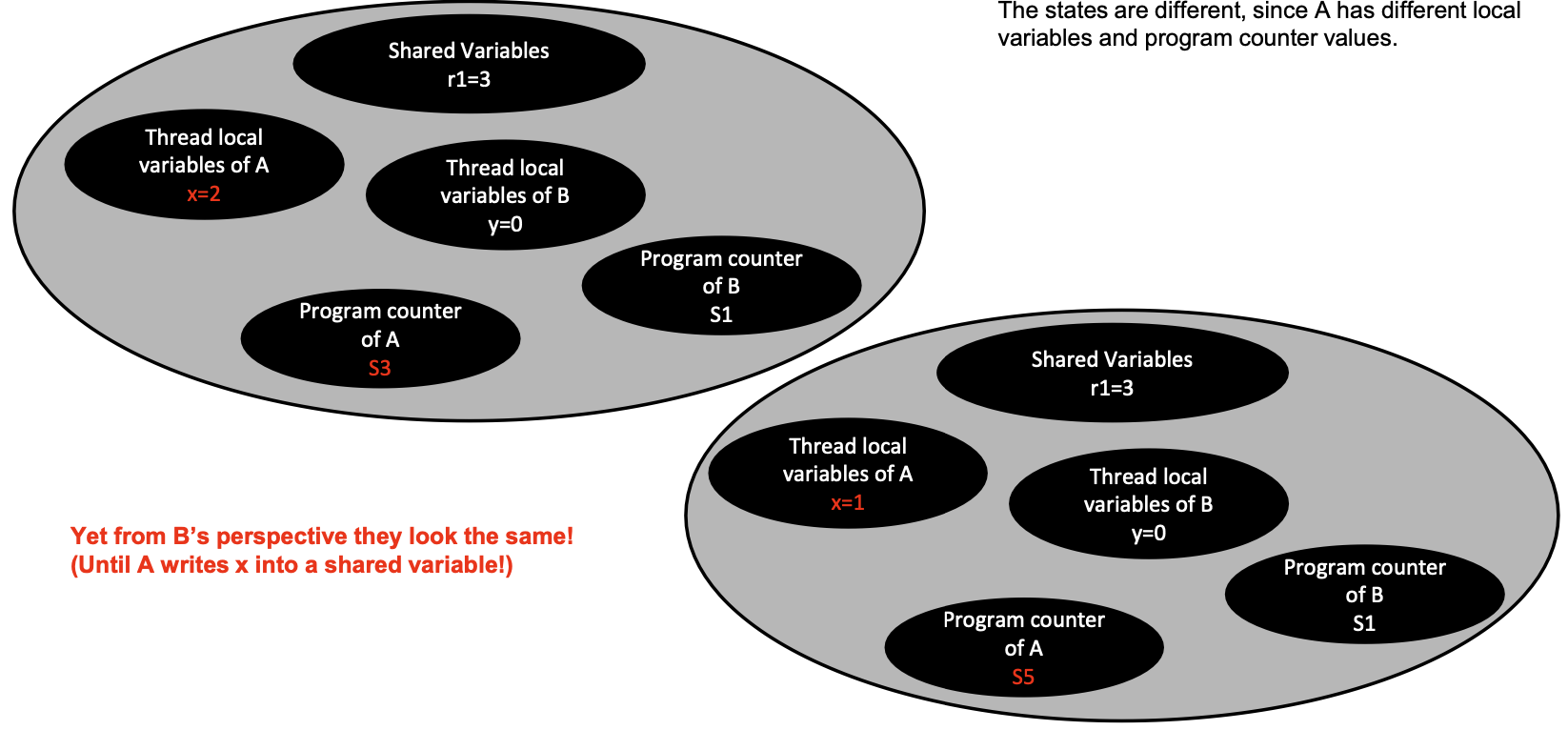

Anatomy of a State (in Two-Thread Consensus)

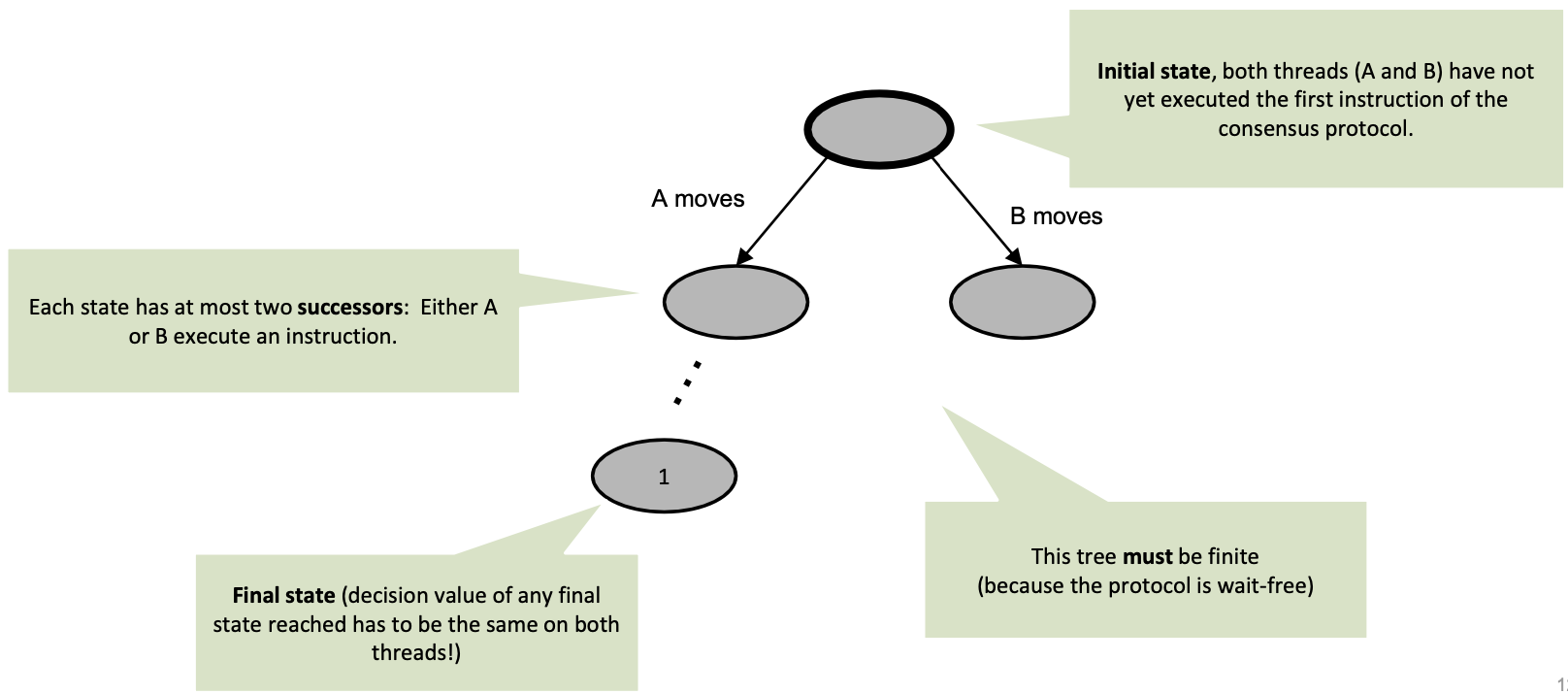

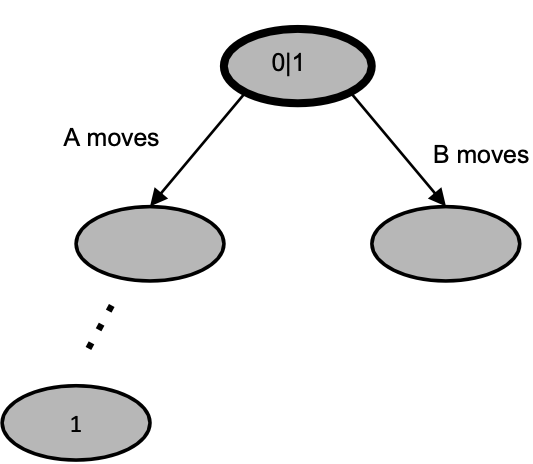

State Diagrams of Two-thread Consensus Protocols

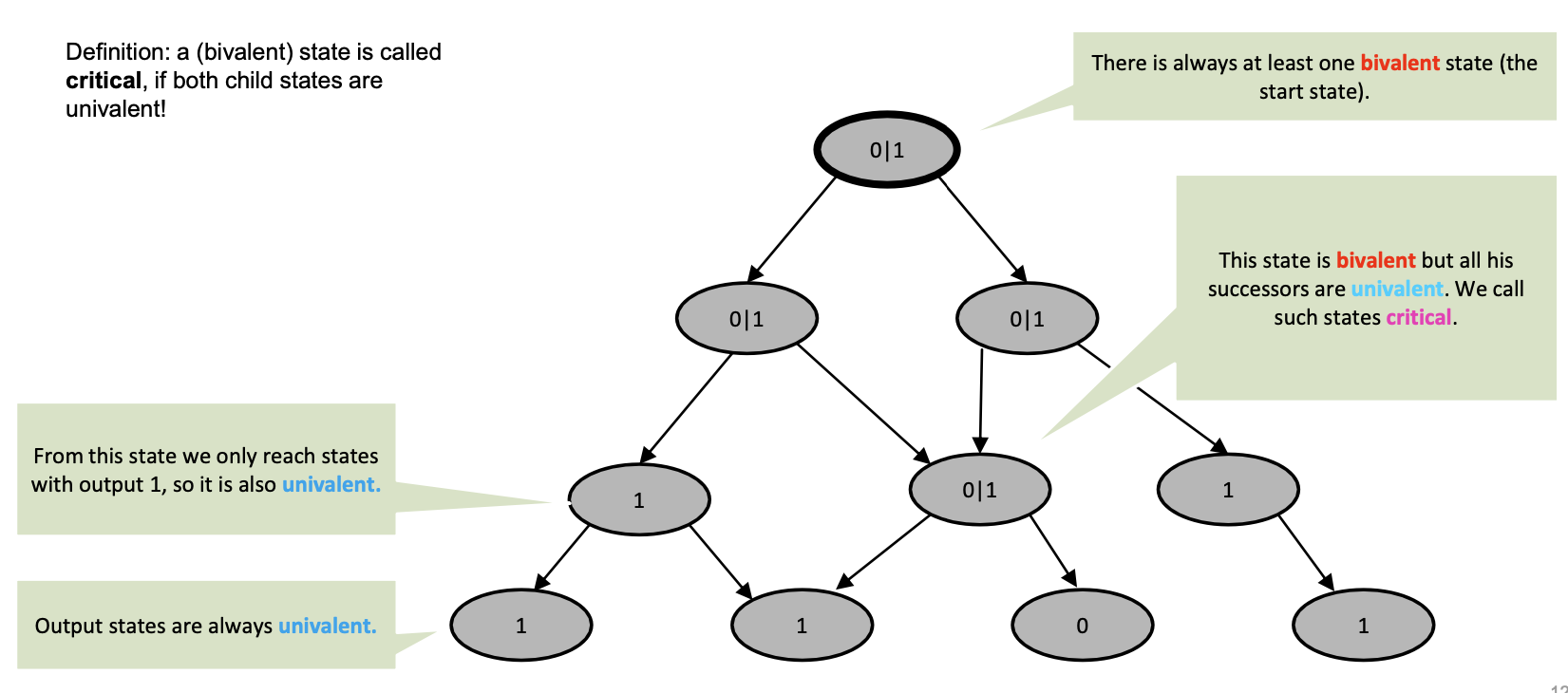

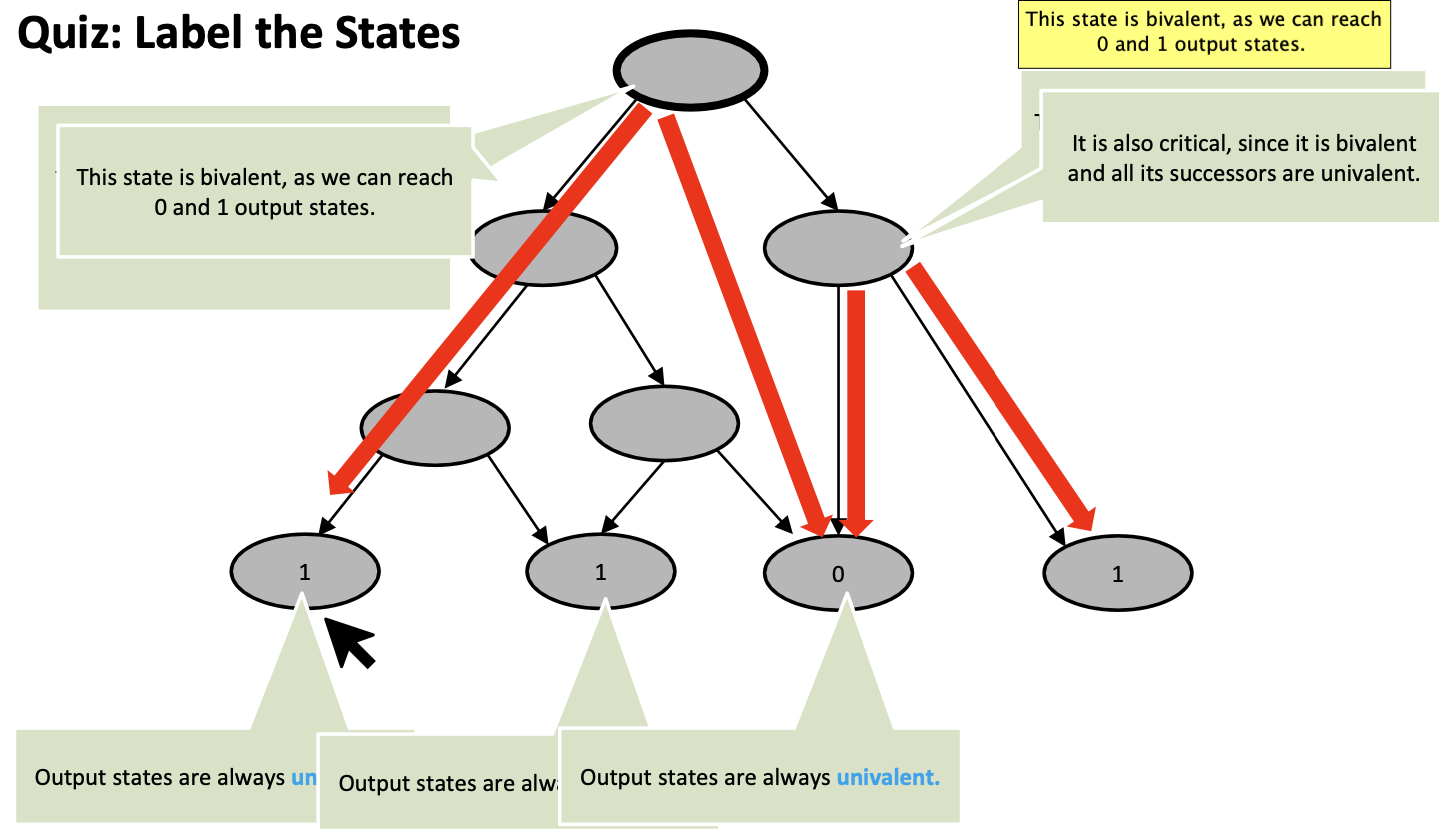

The Concept of Valency

In binary two-thread consensus, threads either decide zero (0) or one (1)

- At some point during the execution (i.e., a state), each thread will “decide” what to return

- We call a state where a thread has decided on one 1-valent and a state where a thread has decided on zero 0-valent

- Undecided states are called bivalent – decided states are called univalent

Lemma 1: The initial state is bivalent

- Proof outline:

- Consider initial state with A has input 0 and B has input 1

- If A finished before B starts, we must decide 0 and if B finishes before A starts, we must decide 1 (because it only knows the thread’s input!)

Thus, the initial state must be bivalent!

Bivalent State

A (bivalent) state is called critical if both child states are univalent!

Lemma 2: Every consensus protocol has a critical state

Proof: From (bivalent) start state, let the threads only move to other bivalent states.

- If it runs forever the protocol is not wait free.

- If it reaches a position where no moves are possible this state is critical.

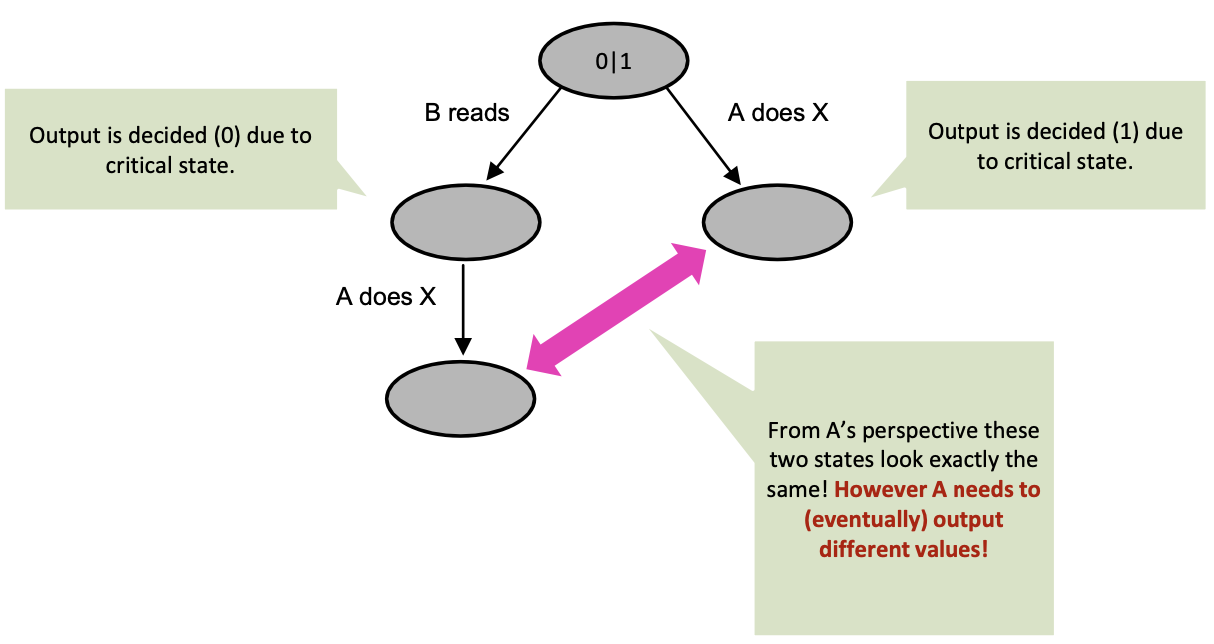

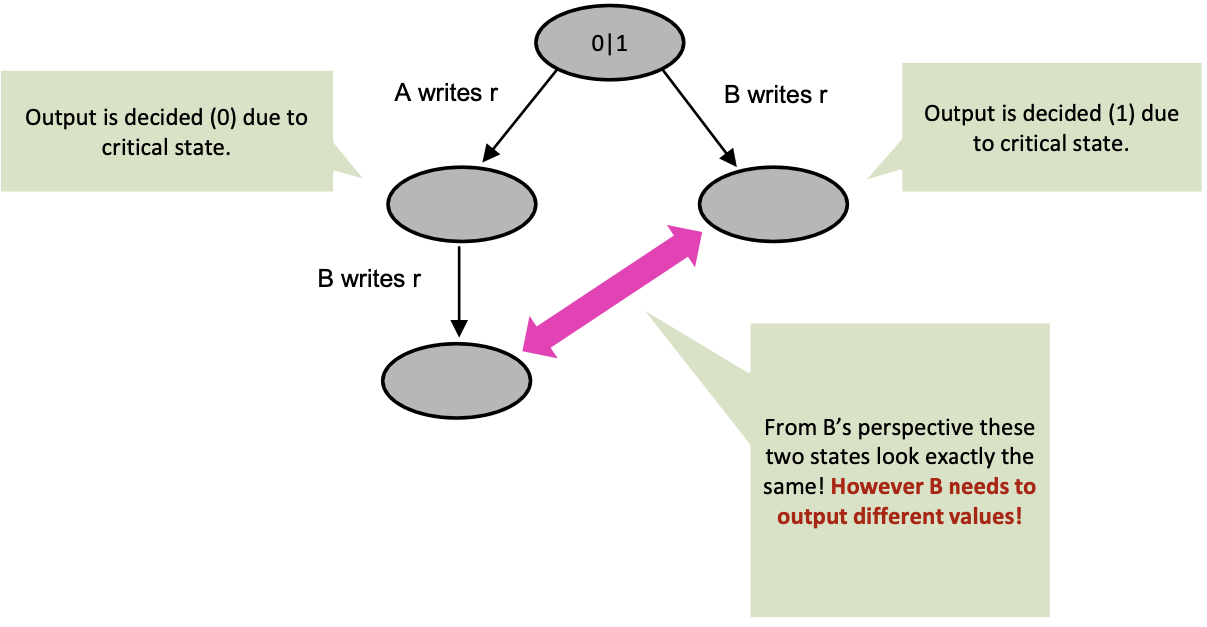

Impossibility Proof Setup – Critical State

Impossibility Proof Setup – Possible actions of a thread

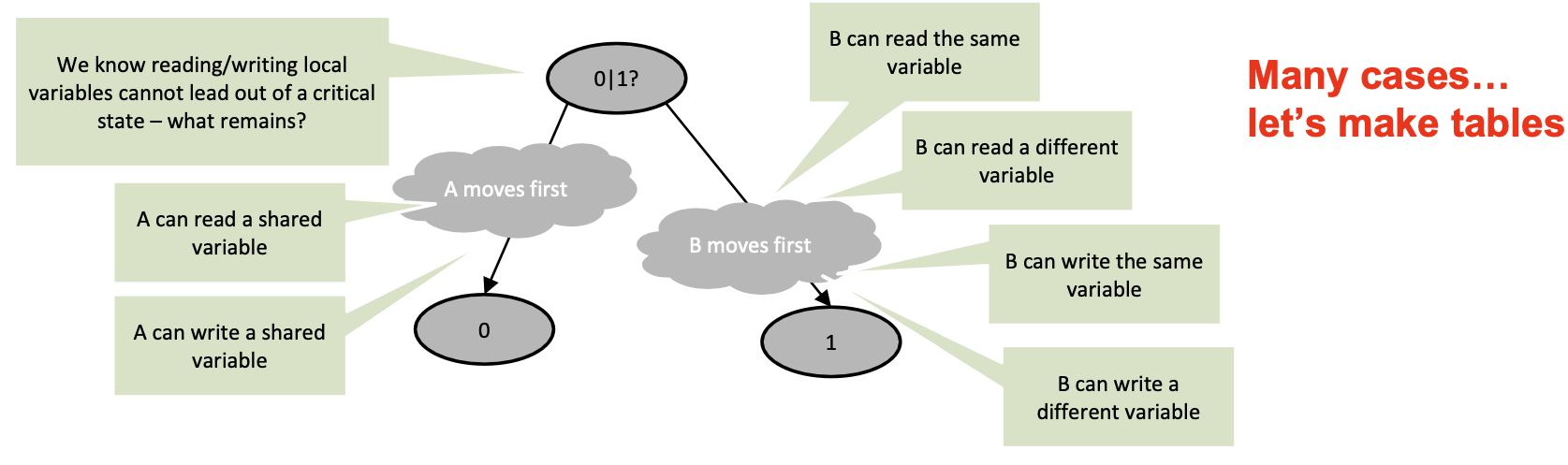

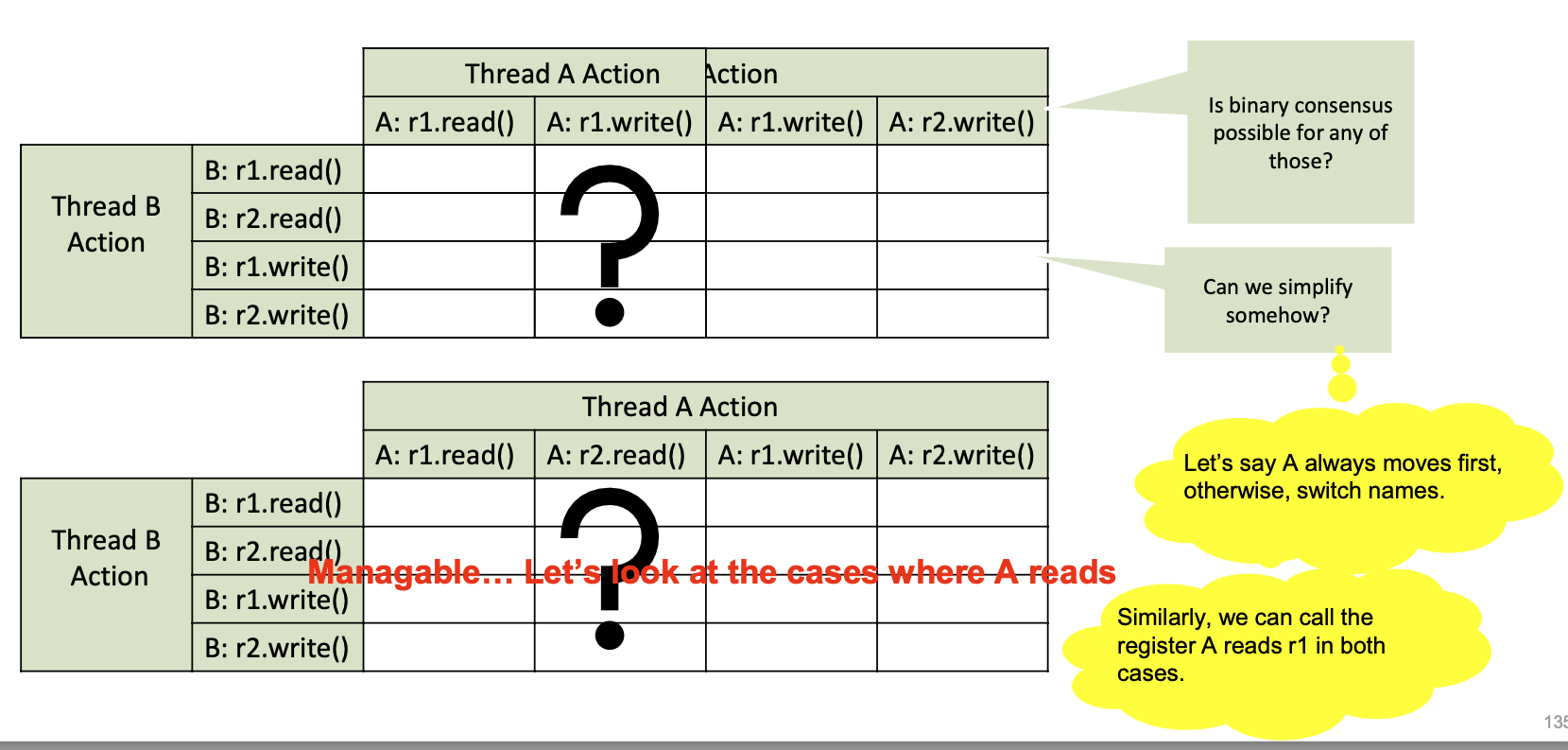

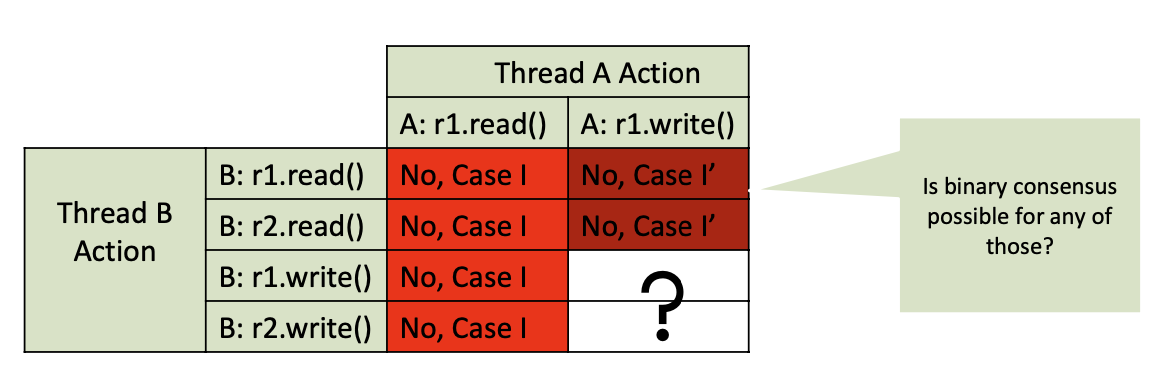

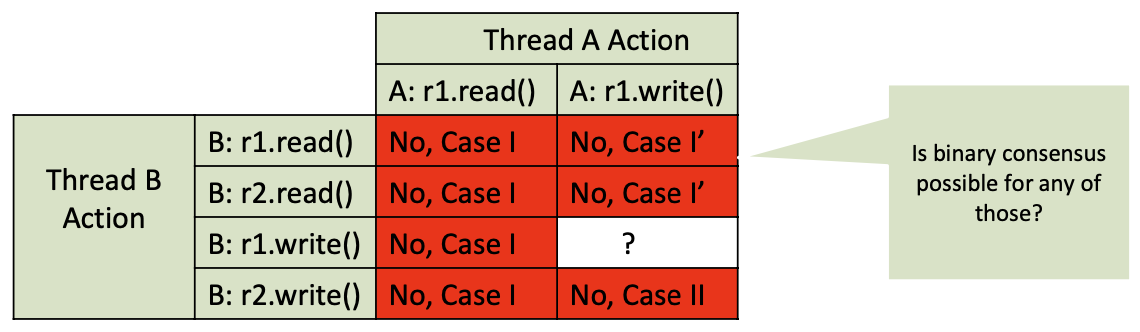

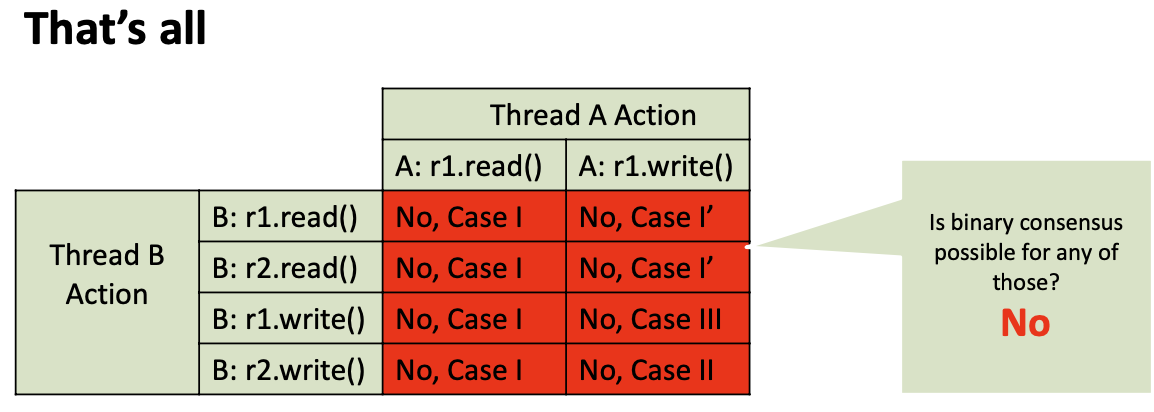

Many Cases to check

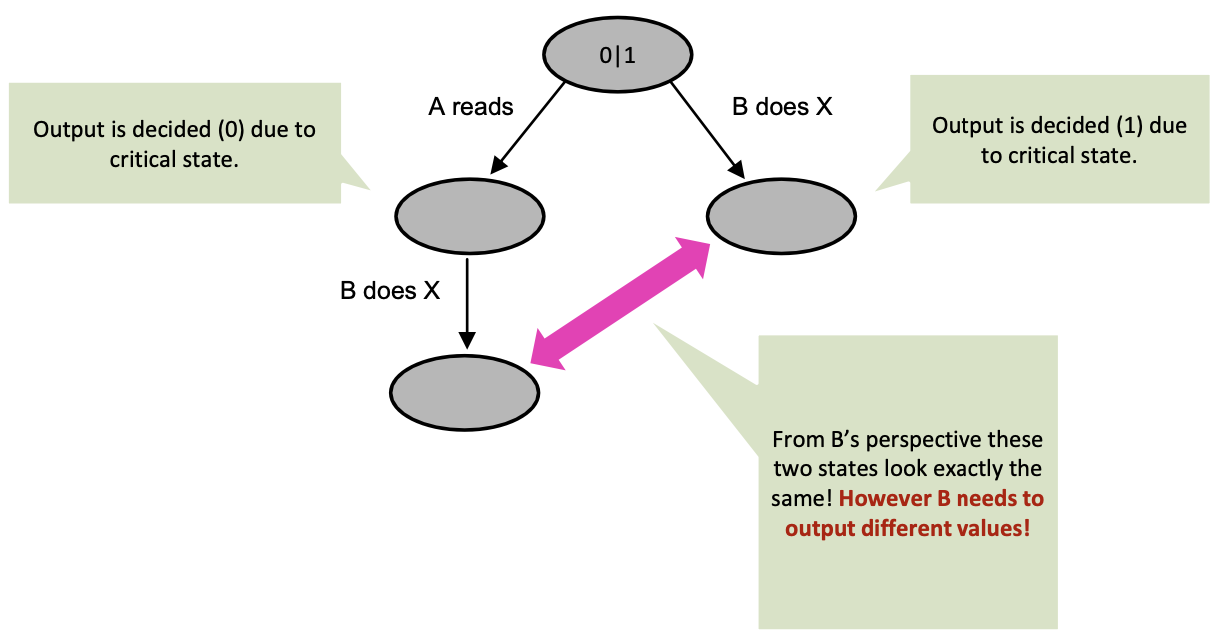

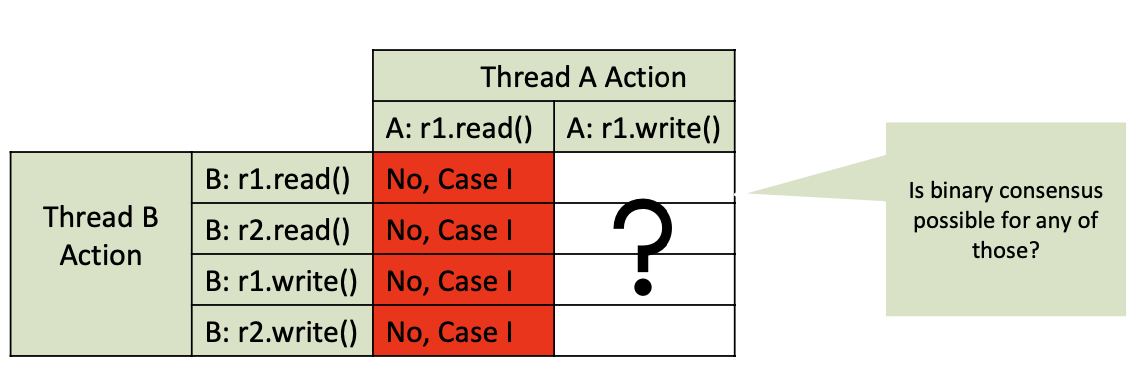

Impossibility Proof Case I: A reads

Impossibility Proof Case I’: B reads

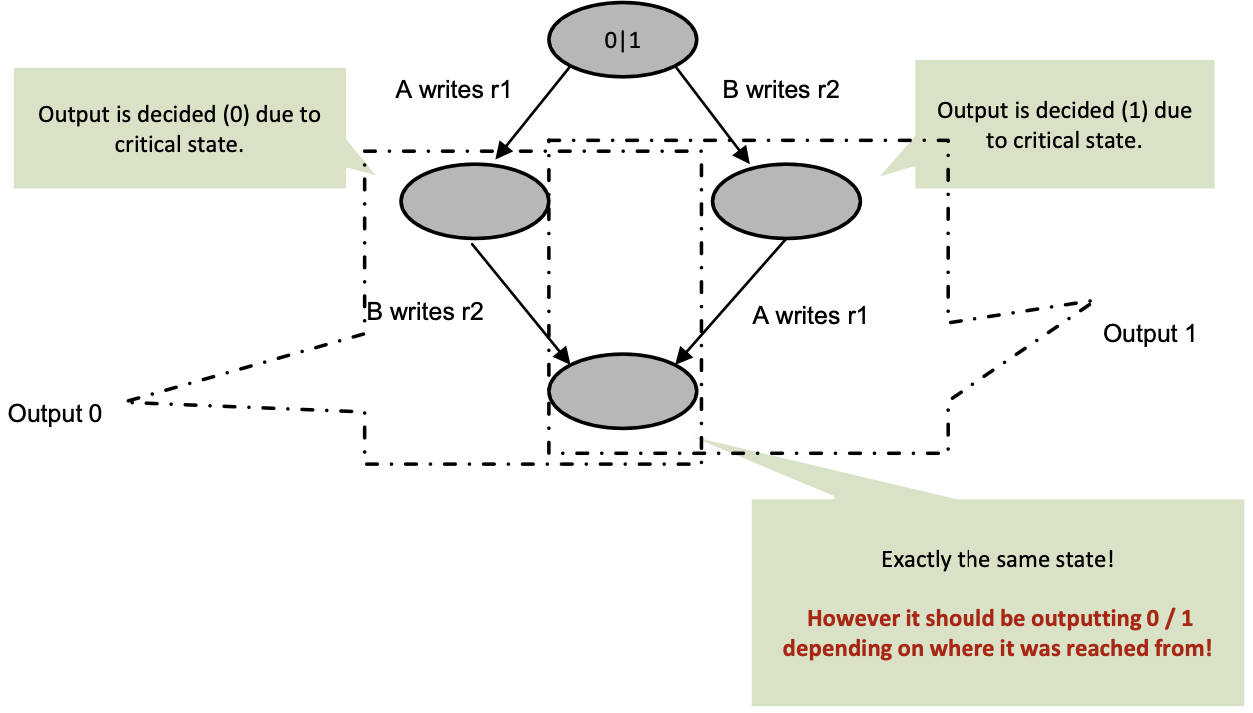

Impossibility Proof Case II: A and B write to different registers

Impossibility Proof Case III: A and B write to the same register

Conclusion

Compare and Set/Swap Consensus

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

const int first = -1

volatile int thread = -1;

int proposed[n];

int decide(v) {

proposed[tid] = v;

if(CAS(thread, first, tid))

return v; // I won!

else

return proposed[thread]; // thread won

}

CAS provides an infinite consensus number

- Machines providing CAS are asynchronous computation equivalents of the Turing Machine

- I.e., any concurrent object can be implemented in a wait-free manner (not necessarily fast!)