Transient Execution Attacks and Defences

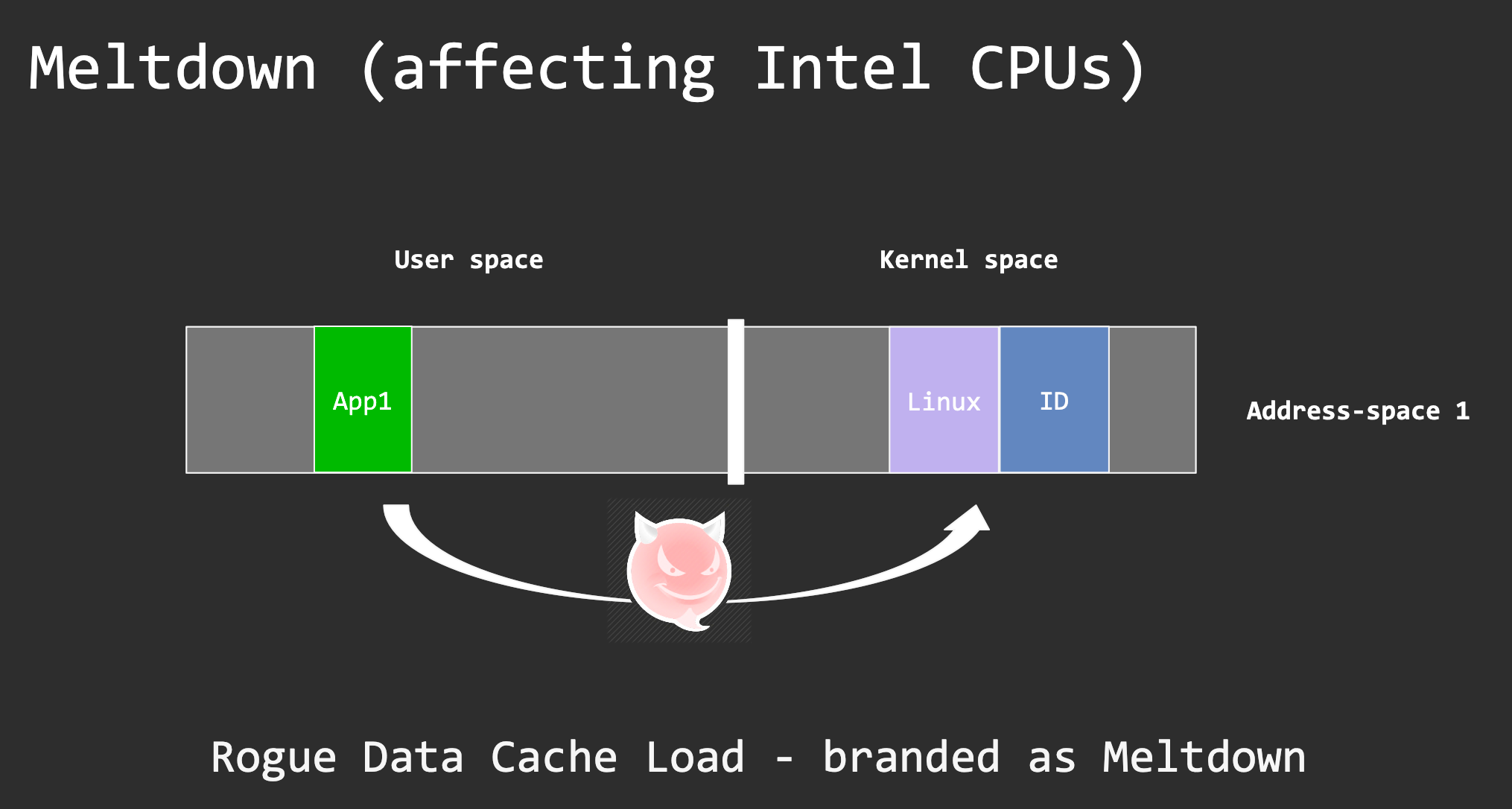

Meltdown: leak arbitrary kernel memory from user mode

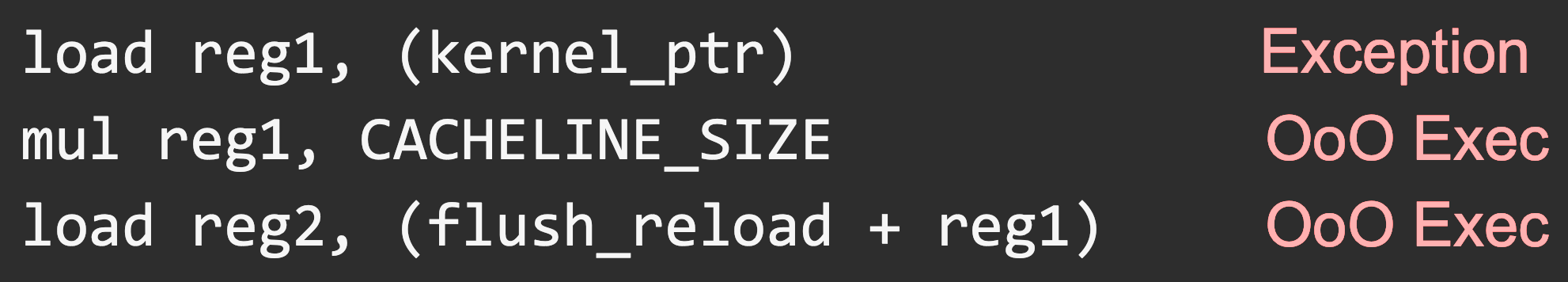

The exploit

1

2

3

4

char flush_reload[256 x CACHELINE_SIZE];

char* kernel_ptr;

flush(flush_reload);

flush_reload[*kernel_ptr x CACHELINE_SIZE];

1

reload(flush_reload);

How come CPU accesses *kernel_ptr from user mode?

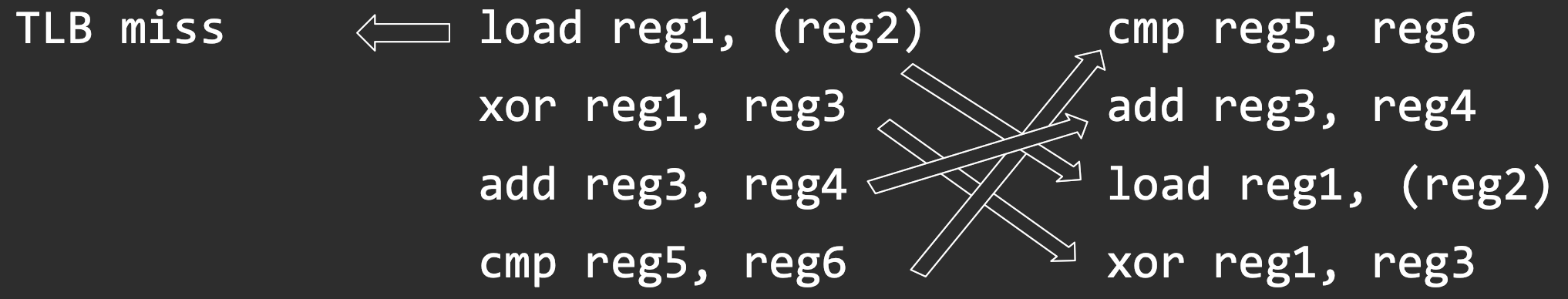

Pipeline stalls

- Some pipeline stages can take much longer ○ load reg1, (reg2) → TLB miss

add reg3, reg4

- Dependencies between different stages

xor reg1, reg2 add reg1, reg3

- Unavailable resources

load reg1, (reg2)load reg1, (reg3)

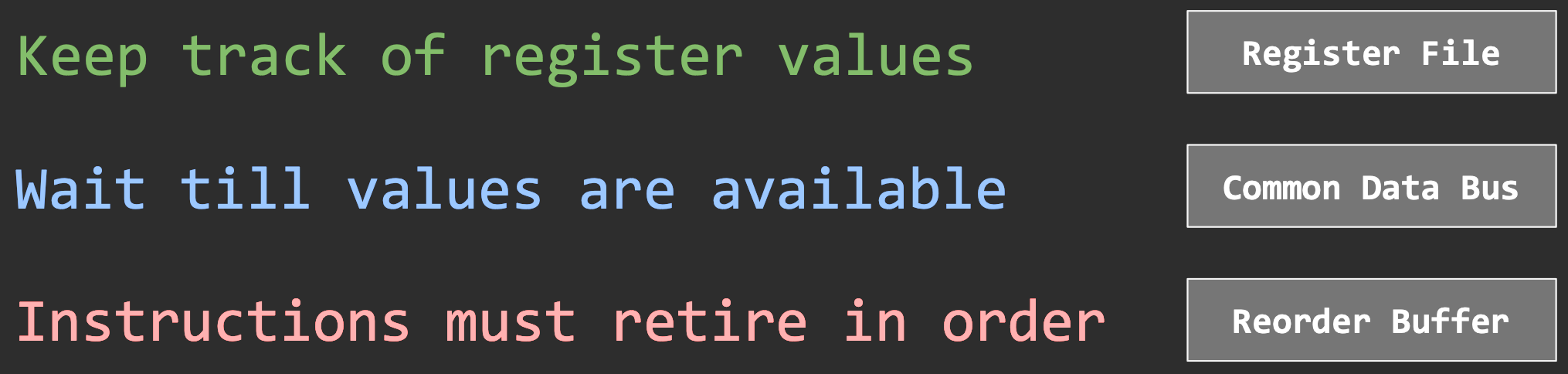

Avoiding Pipeline Stalls

Additional units: multiple ALUs, register file, load/store buffers, etc. Out of order execution

Exceptions in an Out of Order world

Pipeline clears after an exception and out of order instructions are never committed. But the executed out of order instructions may change the micro-architectural state (e.g., caches)

How do we handle the page fault?

Technique 1: PF handling

1) Install a segmentation fault handler 2) Patch the instruction pointer to skip the faulting instruction 3) Return from the signal handler Problem? page fault handling is slow…

Technique 2: transactions

Post-Skylake Intel CPUs feature support for hardware transactional memory known as Intel TSX. Intel TSX suppresses page faults

1

2

3

4

5

6

if (_xbegin() == _XBEGIN_STARTED) {

flush_reload[*kernel_ptr x CACHELINE_SIZE];

_xend();

} else {

abort_handler();

}

How do we reduce the noise?

Speculative accesses can interact with the prefetcher

- Prefetchers (usually) do not operate cross page

*kernel_ptr x CACHELINE_SIZE → *kernel_ptr x PAGE_SIZE- Prefetcher can cause noise in the RELOAD step of FLUSH+RELOAD

- Fool the stream prefetcher by randomizing accesses

1

2

3

4

for (k = 0; k < 256; ++k) {

i = ((k * 167) + 13) & 0xff;

....

}

Life after branch prediction

- Correct prediction? Retire the instructions after the branch.

- Misprediction? Revert the instructions executed after the branch. (similar to exceptions!)

- Reverting the instructions does not revert the micro-architectural state…

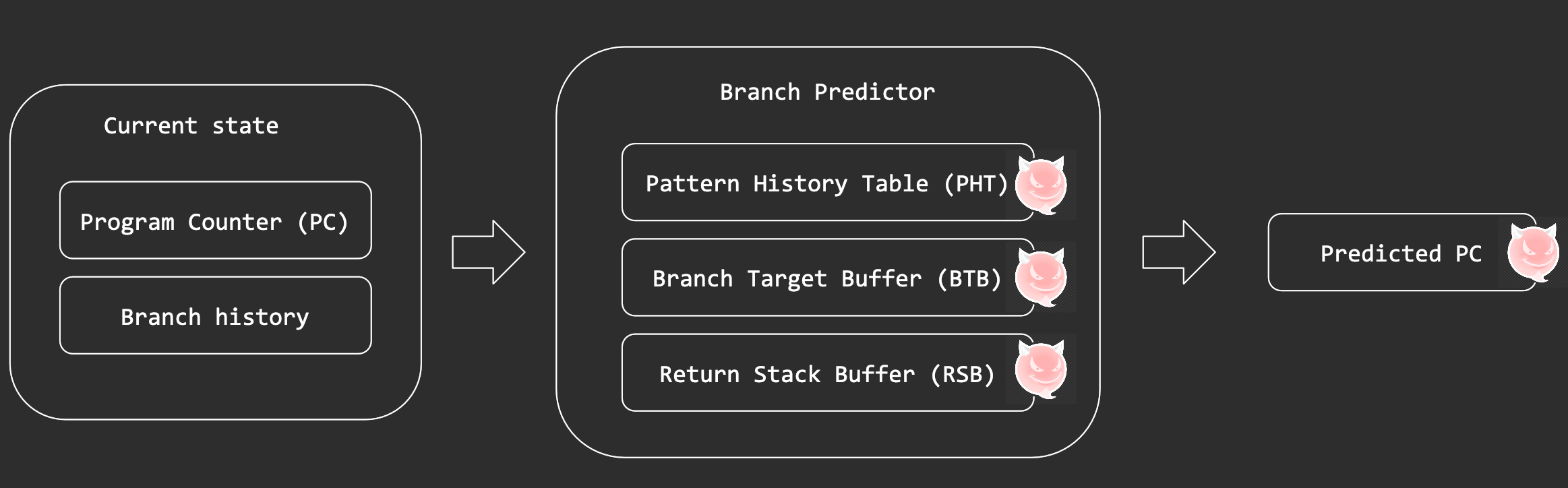

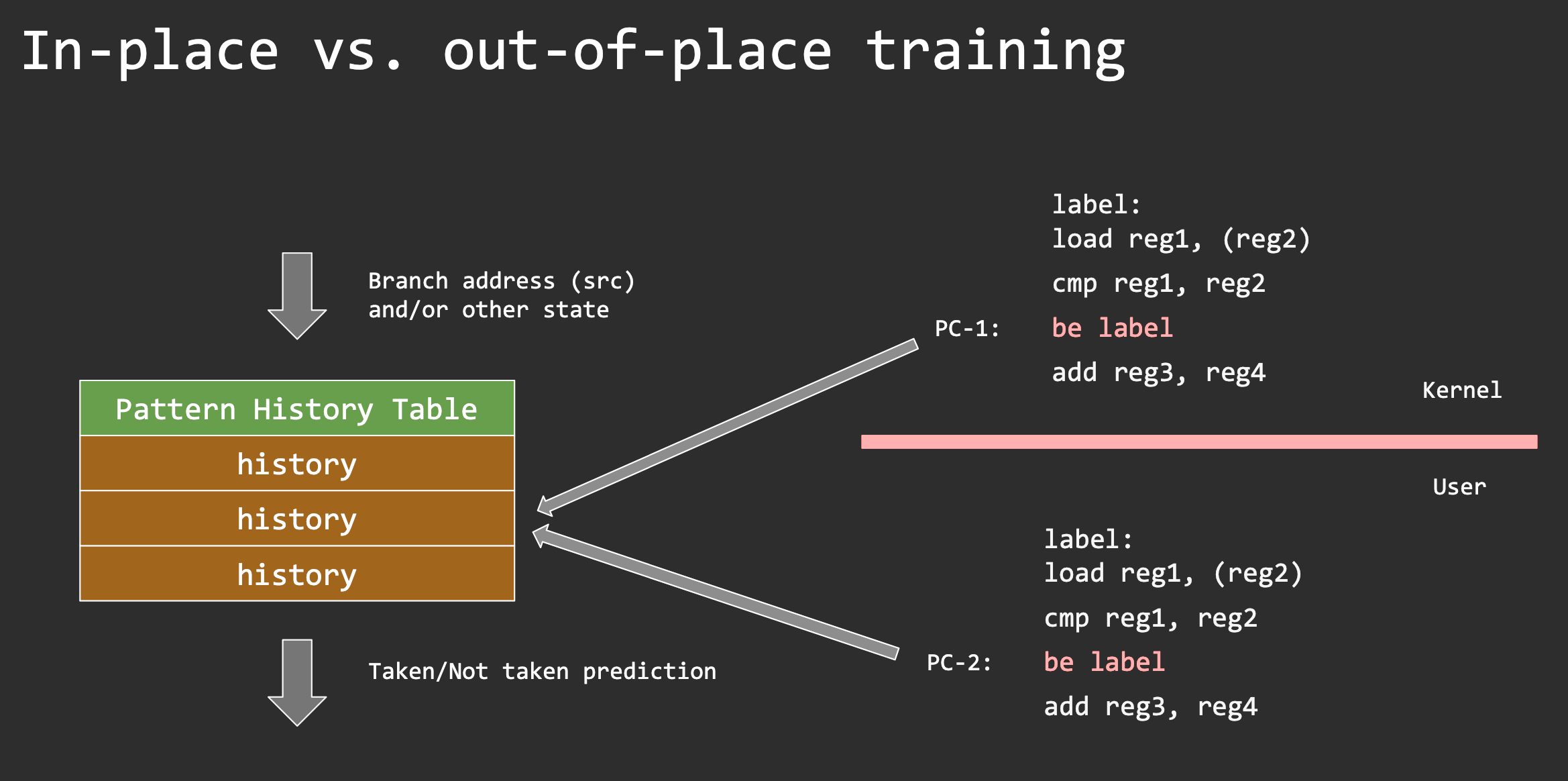

Branch Predictor

Spectre: Leak arbitrary memory in the address space (but not directly across privilege boundary)

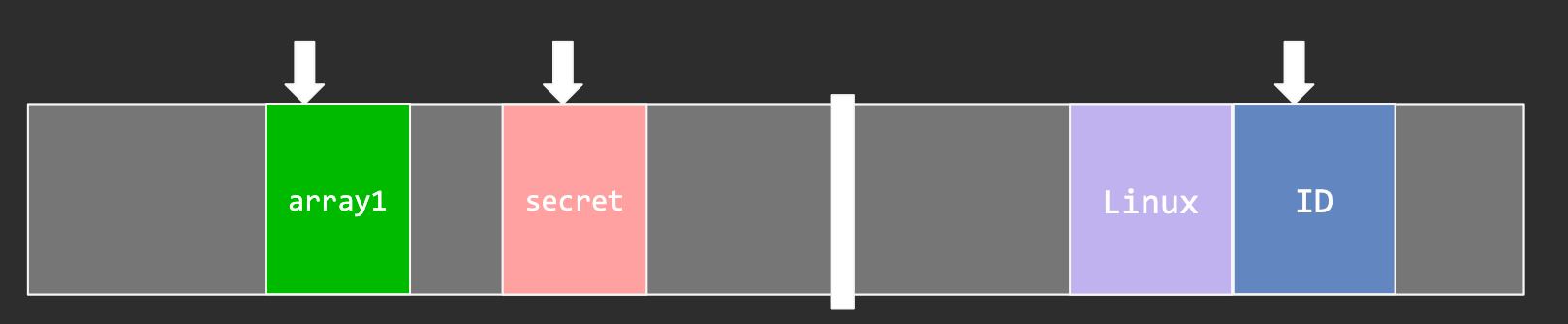

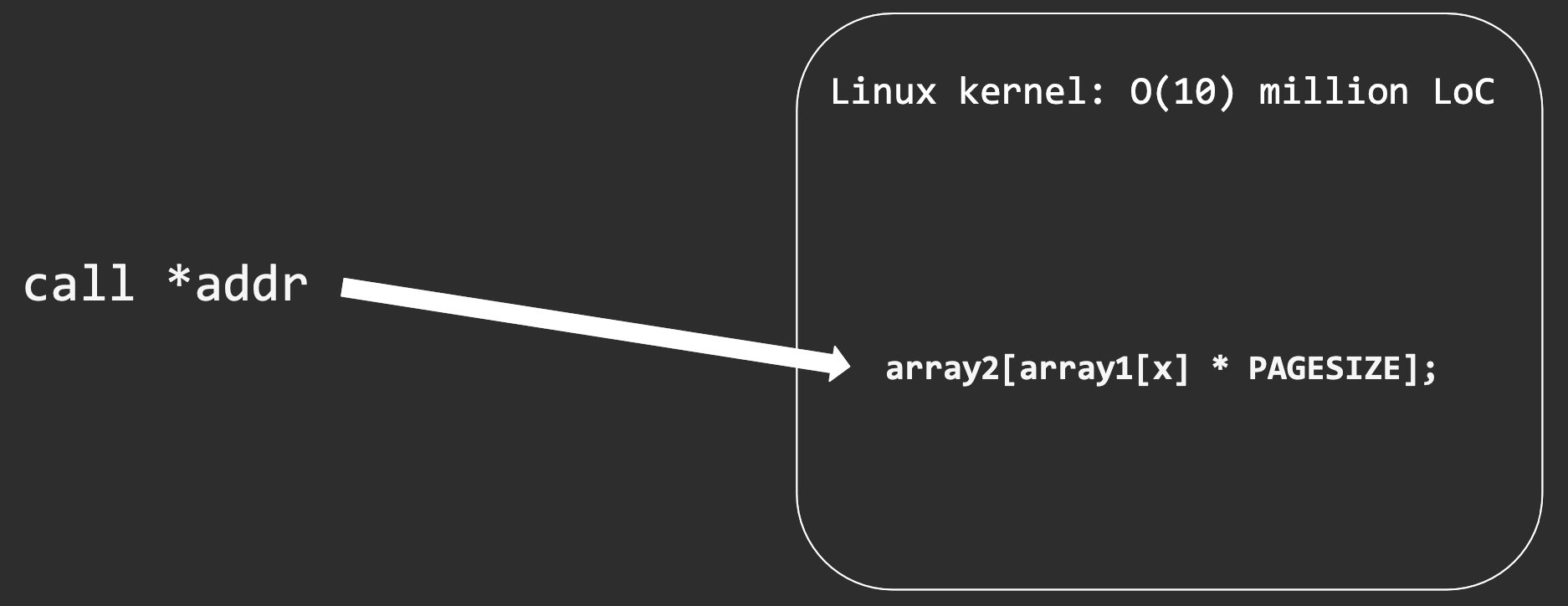

Spectre v1: Bounds Check Bypass

- Train the branch predictor at a given program location to go e.g., Taken

- Flush the data that controls the branch

- Give a branch input that makes it go the other way

1

2

3

if (x < array1_size) {

y = array2[array1[x] * PAGESIZE];

}

array2 can be a FLUSH+RELOAD buffer

- In JavaScript, attacker can create such speculation gadgets

- In Linux kernel, Jann Horn needed eBPF to inject a speculation gadget

- Can be used to leak with #Meltdown (speculation for exception suppression)

Limitation of #Spectre v1

Limited control of the PC in transient execution

1

2

3

if (x < array1_size) {

...

}

We can only leak with very particular speculation gadgets

1

2

3

if (x < array1_size) {

y = array2[array1[x] * PAGESIZE];

}

Unconditionals

Unconditional direct branches

jmp reg or call reg- Resolves fast on misprediction (difficult to queue loads) ●

Unconditional indirect branches

jmp (reg) or call (reg)- May resolve slow due to a potential DRAM transfer → large misprediction window

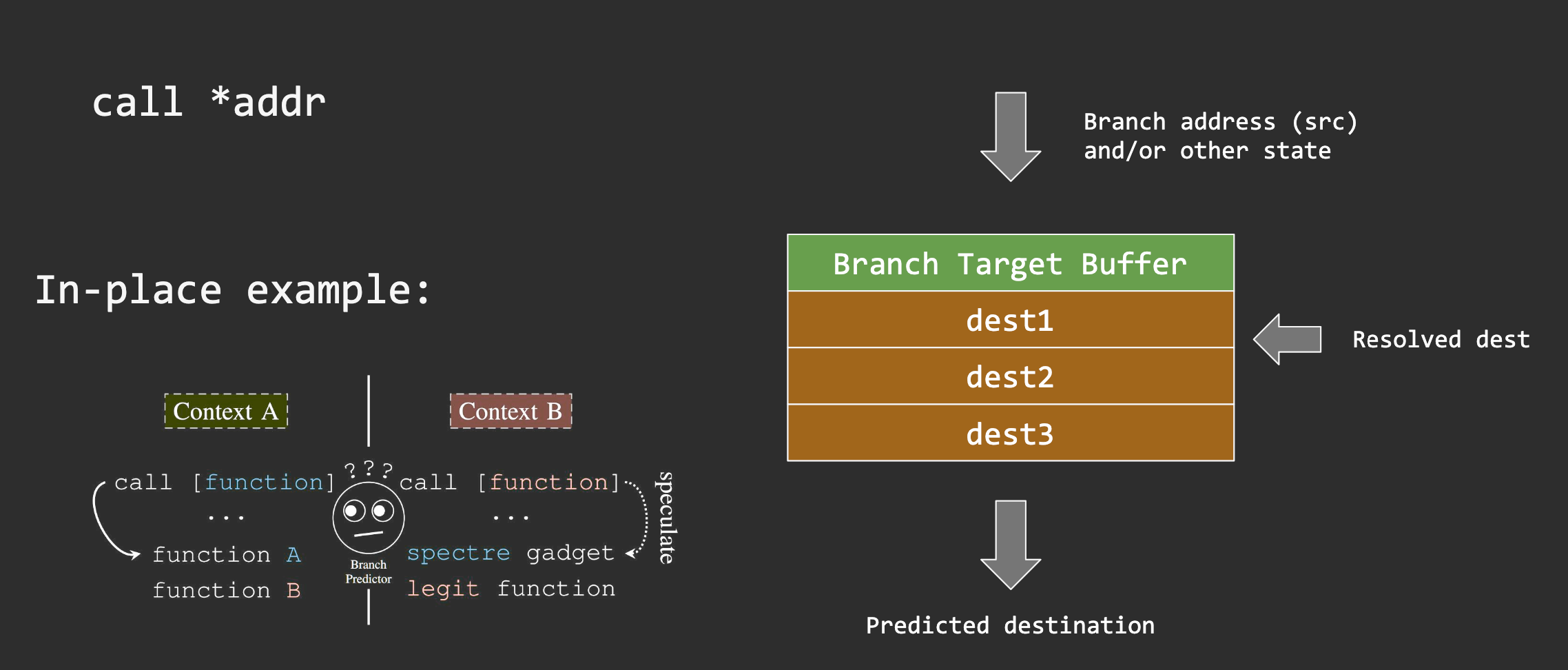

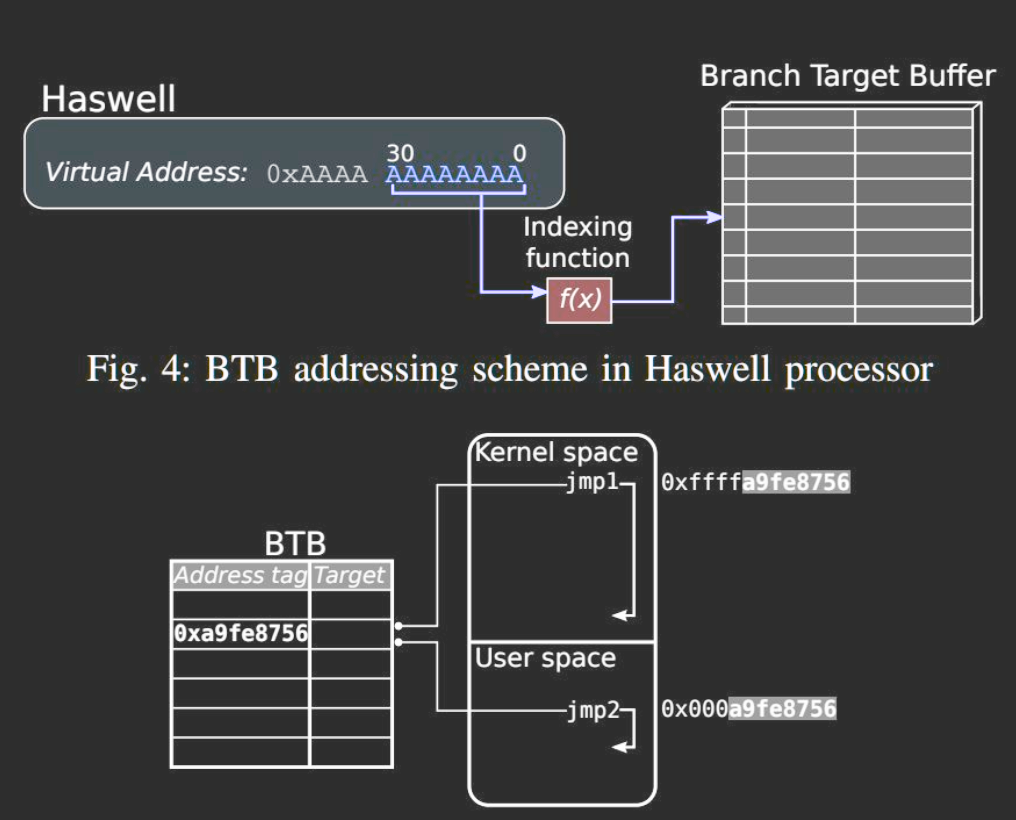

Spectre v2: Branch Target Injection

Collisions in the BTB (out-of-place)

Spectre v2 is more powerful than v1

It provides the attacker with arbitrary speculative code execution

- Code-reuse in speculative execution

- Blanket mitigations

Return instructions

- Every call instruction pushes a return address to the stack

- Return instruction sets the PC to the return address stored on the stack

- Stack is in memory and retrieving the return address can potentially be slow

- Return Stack Buffer (RSB) stores the most recent return addresses in a micro-architectural stack

- RSB has a limited size and can underflow…

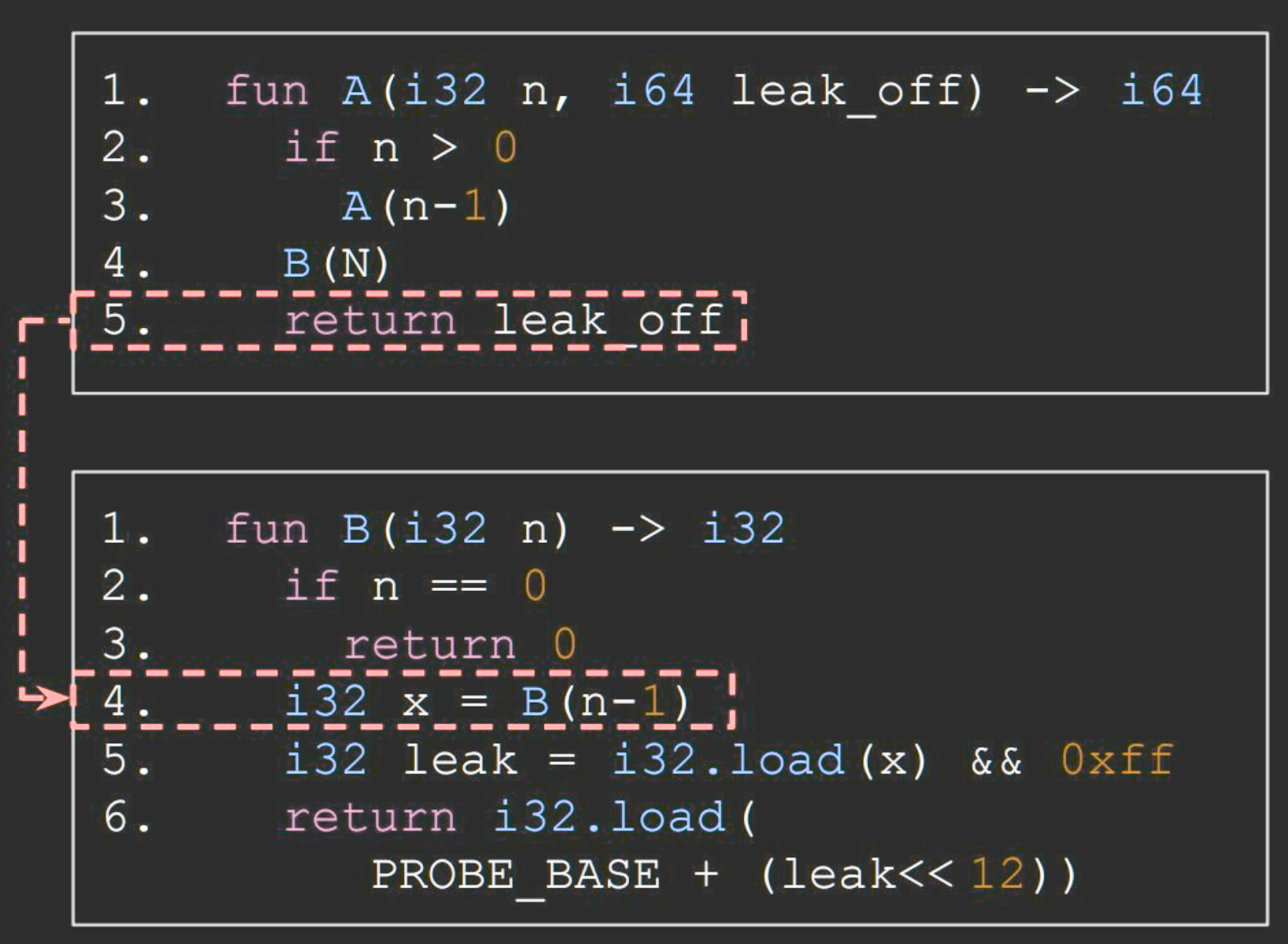

Limitation of Spectre RSB

- Requires deep call stacks

- Disclosure gadget needs to come right after

1

2

call ... call (reg)

DISCLOSURE GADGET

- Possible to craft in JavaScript

- Difficult to do in the kernel (or is it…)

Mitigating Spectre

1) Spectre v1 (Bounds Check Bypass)

lfencestops speculation- But it also serialises all the other loads in the pipeline

- → expensive

1

2

3

4

if (x < array1_size) {

asm("lfence");

y = array2[array1[x] * PAGESIZE];

}

SMAP instructions automatically stop speculation

For v1 and v2

- Pointer masking on every memory access. Pointers cannot go out of bound.

- Early JavaScript mitigation in chrome (later replaced by site isolation)

- Default in Firefox

- Pointer masking on untrusted input

- Linux kernel (array pointer sanitisation)

- Browsers disabled timers (partial mitigation)

- Process-based site isolation (e.g., Chrome) and flush the branch predictor state on context switch

2) Spectre v2 (Branch Target Injection)

Intel released microcode update with instructions to partially flush the BTB (IBRS)

- Too slow, did not get adopted. (Until Retbleed)

- Retpoline: blanket compiler-based mitigation that turns all indirect calls into a protected return

3) Spectre RSB (RSB poisoning)

- We do not want kernel return addresses in the RSB when in user space. Why is that?

- Stuff the RSB with useless return address when switching to user-mode or between different processes

- Is it necessary to stuff the RSB when switching to kernel from user-mode?

Summary

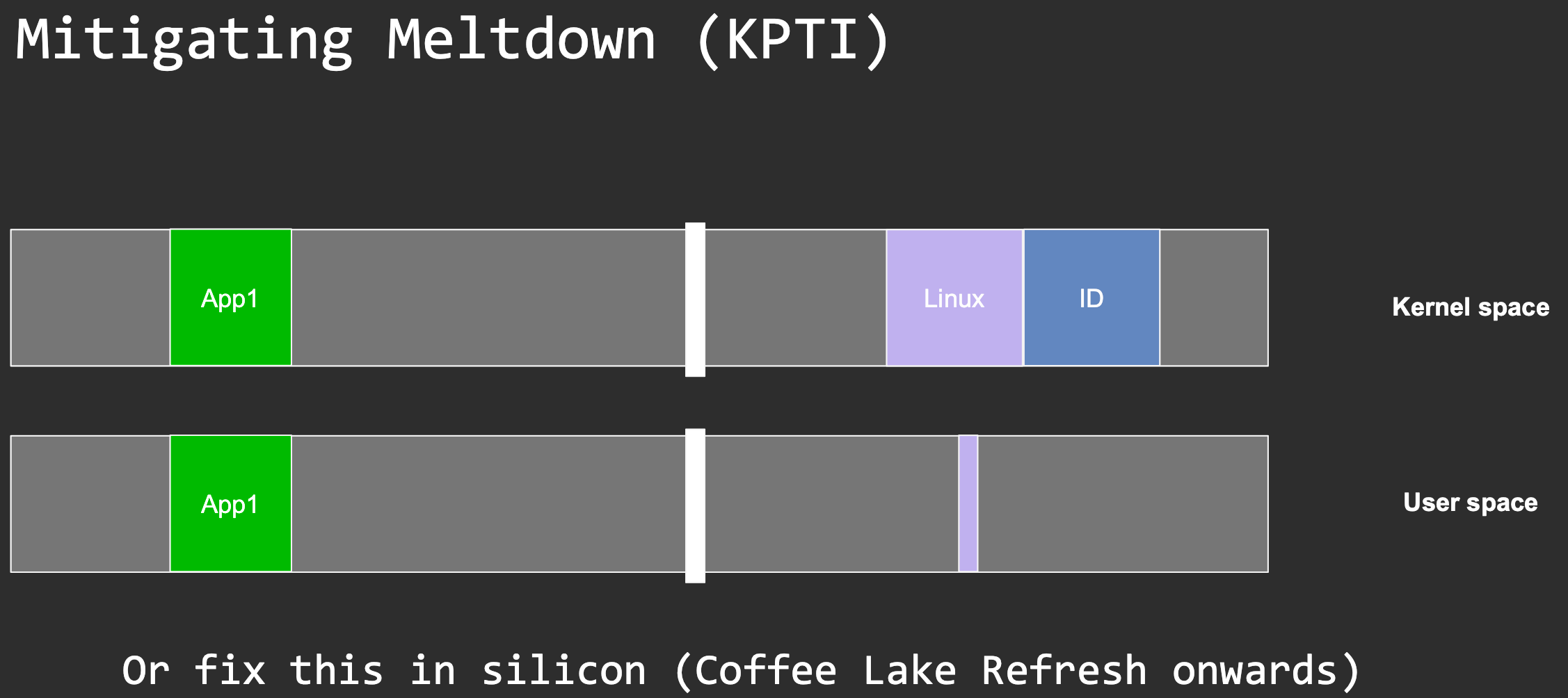

Meltdown exploits a bug in Intel’s out-of-order engine, allowing the privileged kernel-space data to be read from unprivileged processes. Spectre poisons the branch target buffer (BTB) and thus tricks the branch prediction unit into bypassing bounds checks in sandboxed memory accesses, or even triggering arbitrary speculative code execution in different processes on the same core.